Commentary

-

Micro/Macro Readings

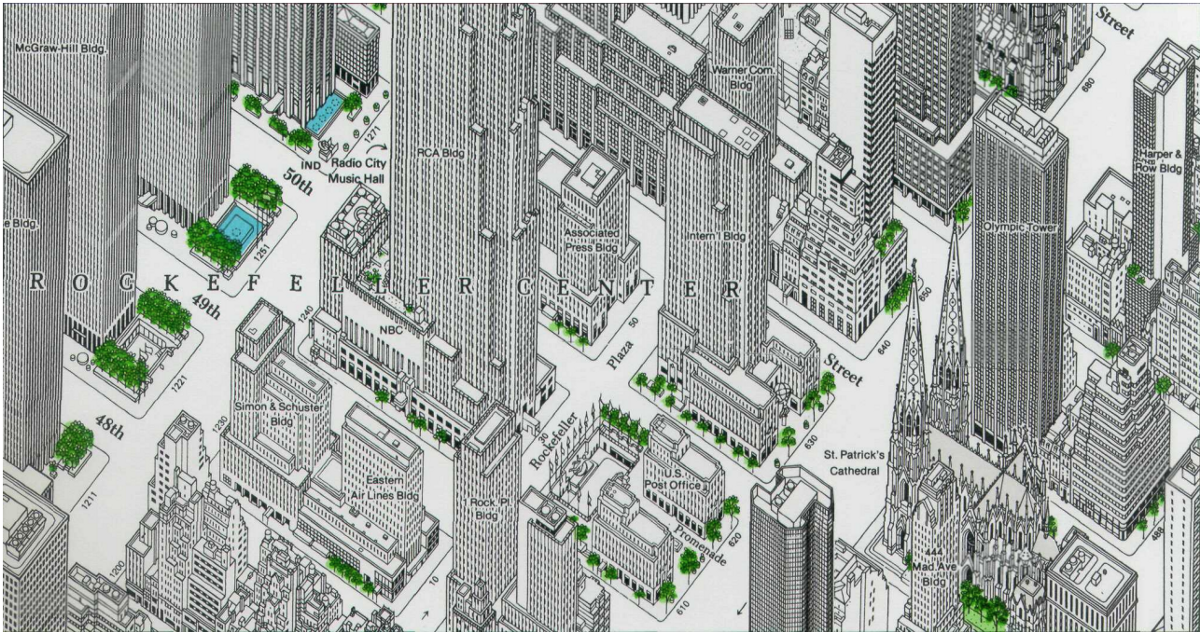

The examples Tufte gives in Chapter 2 of Envisioning Information all contain immense amounts of data. In the axonometric map of midtown New York, there are labels for ever single street/avenue, depictions of every building/tree/etc. When the viewer steps back they can maybe identify larger buildings, but mostly see a big picture of the layout of Manhattan, but then they can also move closer and see the individual buildings that are distinct from each other. Tufte points out that the micro/macro technique allows viewers to see all the data at once, instead of spread over multiple diagrams or pages, making it easier to draw conclusions and make comparisons. Viewers also have the option to look closer and see individual data points. When describing the stem and leaf diagrams, Tufte writes, “the same ink serves more than one information purpose.” The “same ink” shows the message of the data set overall, and also the individual data points and what they represent.

The Vietnamese Veterans Memorial example resonated with me the most. It was really interesting that the critical design decision to order names by date of death instead of alphabetical order made such a big difference in the way people interpret the memorial and information. Ordering the names by date allows the data to tell a story and gives more meaning to each individual name, while still retaining the impact of the immense number of names all together.

-

Tufte chapter 2- micro/macro

Macro design allows the viewer to have more freedom of interpretation, taking in an overall theme, concept, or data set that is conveyed well and easily understood (arranging blocks of text in a specific shape could be an example of this). The micro elements of the design are what allow the reader to dive deep into the nuances of the piece and have a more personalized and rich experience of the information presented (for example, using different textures, fonts, or clarifying text). If used together, these can make a design multi-leveled, profound, and complex; easy to navigate yet detailed and thorough.

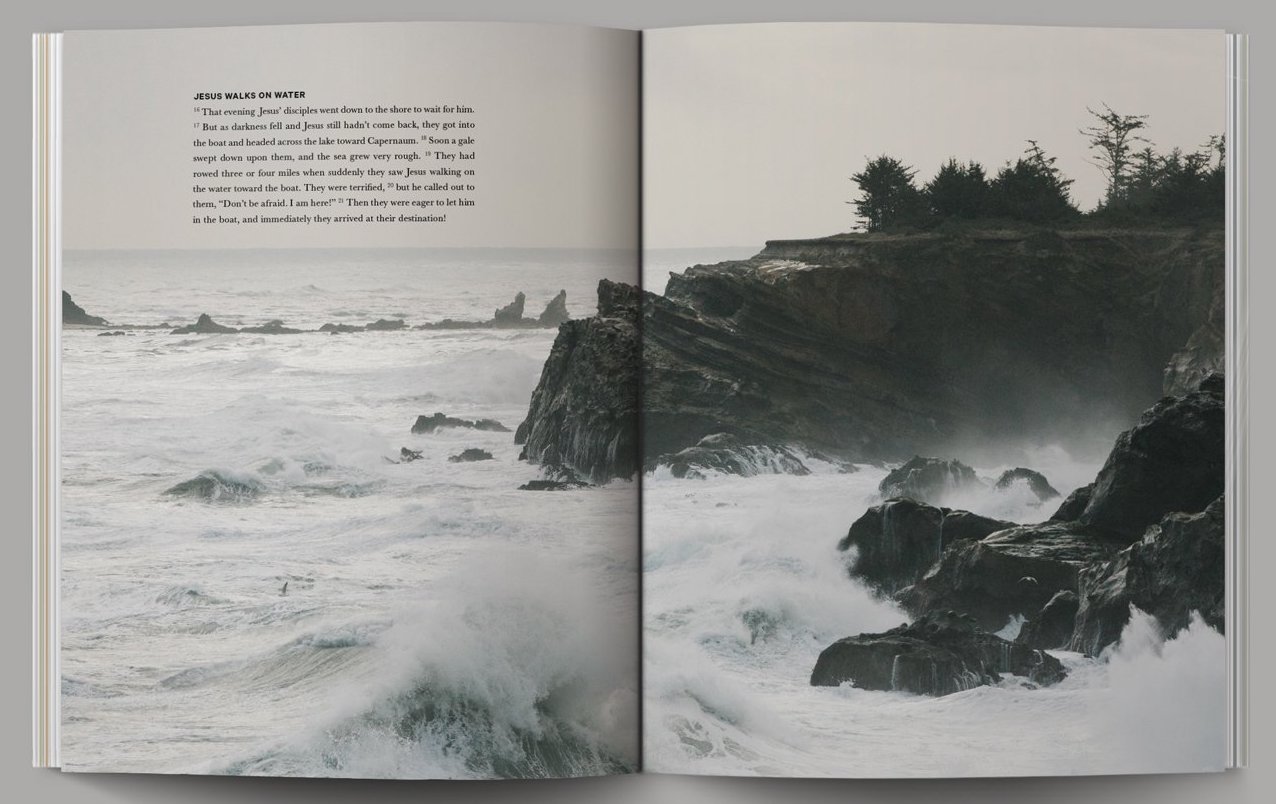

One of the examples of effective use of micro/macro design that I found really interesting was the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C From a far, this piece looks like a black long wall with grey texture, however, when you look up close, you can discern the names of the dead soldiers that lost their lives during the Vietnam war. Both of these combine to display both the magnitude of the deceased and the individuality and value of each fallen soldier.

-

Tufte Reading Chapter 2

In this reading, Tufte discusses the principles and challenges of visualizing data complexity, particularly in a way that facilitates both a clear macro-reading and micro-reading. It seems that one key principle Tufte focuses on is the importance of properly organizing fine, complex detail to exhibit the overall picture clearly—”to clarify, add detail”.

We can see in the example of both the midtown Manhattan map (Constantine Anderson) and the Map of Paris (Bretez-Turgot), that the dedication to depicting cityscapes in precise, exquisite detail in an orderly way produces new opportunities for readings, as well as challenges/questions. Some new opportunities for readings include allowing readers to get an essence of the city at a glance (for manhattan, we see many high rise buildings and some greenery; for paris, we see more consistent heights of buildings and many waterways) as well as allowing readers to zoom in on the fine information in specific parks, windows (creating an opportunity for readers to develop their own personal stories about the data). Some challenges that come with the “to clarify, add detail” strategy include cost of time, resources, resolution, which are seem to be the tradeoffs with clarity of a design according to Tufte.

This also brings about questions regarding some assumptions that Tufte might be making about the viewers of the design. “High-density designs also allow viewers to select, to narrate, to recast and personalize data for their own uses. Thus control of information is given over to viewers, not to editors, designers, or decorators.” It appears that Tufte is in favor of sharing all the possible data in a clear, organized way with the viewer, and to make the viewer do the hard work of analyzing the information-thick world. Although humans have the capacity to do this work, I wonder is it always helpful to share the richest possible properly arranged data with a viewer, and when is it better to guide the viewer by not share every part of a high density dataset? (In the case of the manhattan map, is the fine-detailed map helping a viewer beyond providing an interesting, personal experience? what about if the viewer wishes to navigate based on this map?)

Tufte’s comments about how the simpleness of data + design ≠ clarity of meaning reminds me of his comments on chartjunk—Why does Tufte seem to prefer and find high densities of (well-organized) numerical data clarifying, but despises and find less numerical/more illustrative data extraneous and cluttering?

-

Smallest difference to the biggest impact

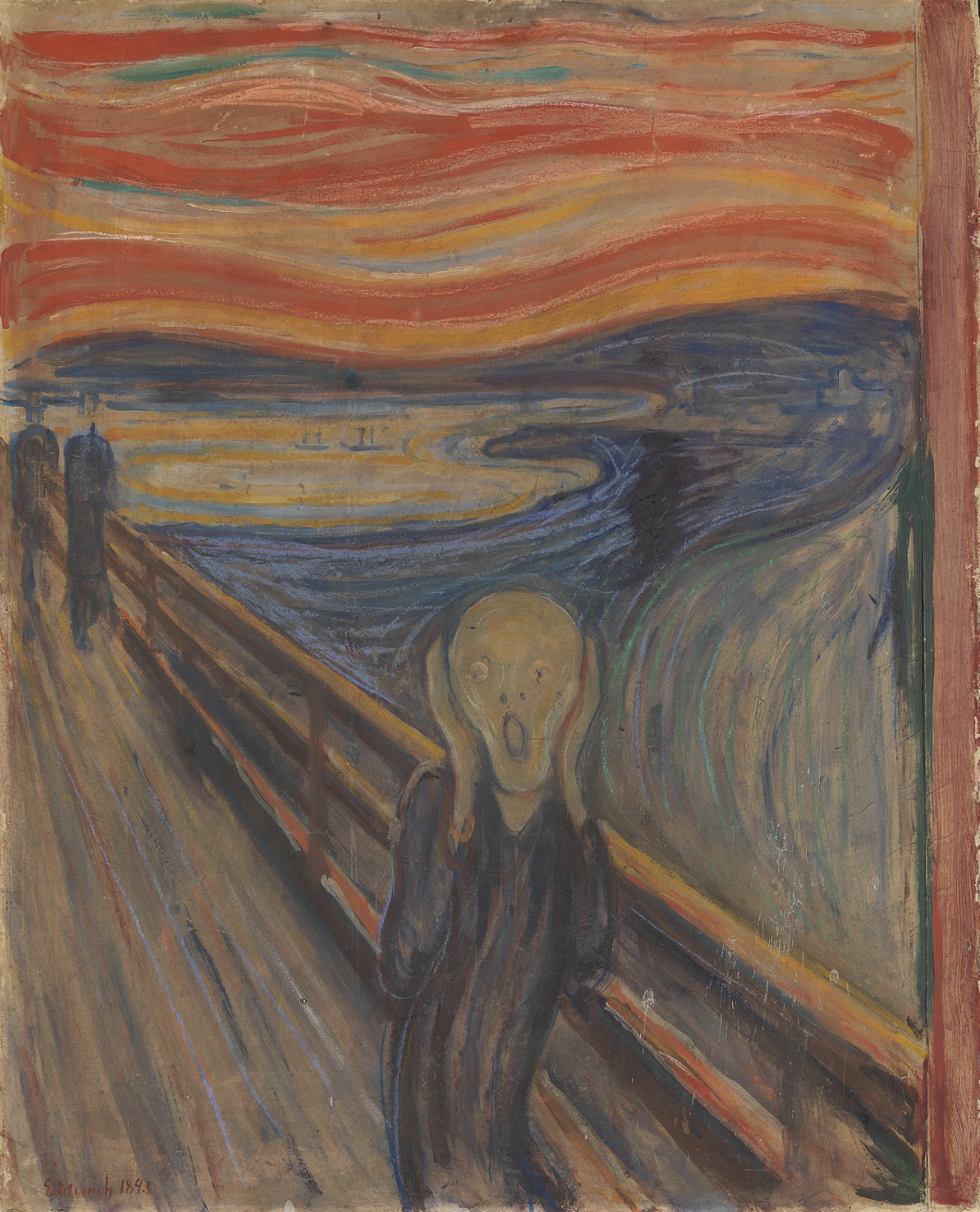

The main perspective that speaks volumes from this reading is how the smallest difference in design can make the largest difference in meaning. Maya Ying Lin’s Vietnam Memorial offers a powerful example. By listing the soldiers’ names alphabetically, their story doesn’t manifest as profoundly. Alphabetically, the memorial turns into a list, but by reordering, it gives families and visitors a better understanding. Hunting through names of a loved one becomes reminiscent of searching for a soldier on a battlefield, but you have zoom in on the names. Combining micro/macro features makes a kind of treasure hunt for viewers. There’s more detail to be uncovered, and more of a story to unfold the closer you look. Impressionists utilized this concept at the turn of the 20th century; the further away you are from their paintings, the more of an object you see. The closer you get, the better you can appreciate their brushstrokes and the detail of their paint. In the attached example, the art is an eye. However, a wedding tale can be seen within the pupil. This artist strives to tell Wedding Days using the eyes of guests. To Tufte’s point; a closer perspective offers another facet to an overall story. Howeverm like the map of New York, if you zoom out, the details fade away to the larger narrative.

(Peter Adams-Shawn)

(Peter Adams-Shawn) -

Micro/Macro Data Complexity

Tufte’s primary argument in this chapter is to “add detail to clarify” for many types of data complexity. At first, this seemed to go against what we had read about chartjunk and designing to capture the essentials, but it was clarified for me when he wrote “Clutter and confusion are failures of design, not attributes of information.” I think the examples he examines lend themselves particularly well to this paradigm, but I don’t know if it’s always generalizable. For the maps he examines, because maps are fully continuous and the scale can be decided on, the scale and data labeled on it can always be chosen to capture as much data as possible without being overwhelming or cluttered, and we see this executed really well in the Tokyo mesh maps. This technique also works really well when the data points cannot be summed up or summarized, such as with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where every name is a full life that was lost, so simply laying out every single one communicates scale without trivializing any soldier. While all these examples use the principle well, I worry that the advice is misleading because often it is hard to create a data-rich visualization while also communicating a specific point. If the data is just being published for wide use and can allow interactivity, detail is incredibly useful, but often data visualizations are made to communicate a specific idea which can be lost in high levels of detail. Still, this point is important to keep in mind to ward off instances of over=simplification, and make visualizations as dense as makes sense for every given story.

-

micro and macro

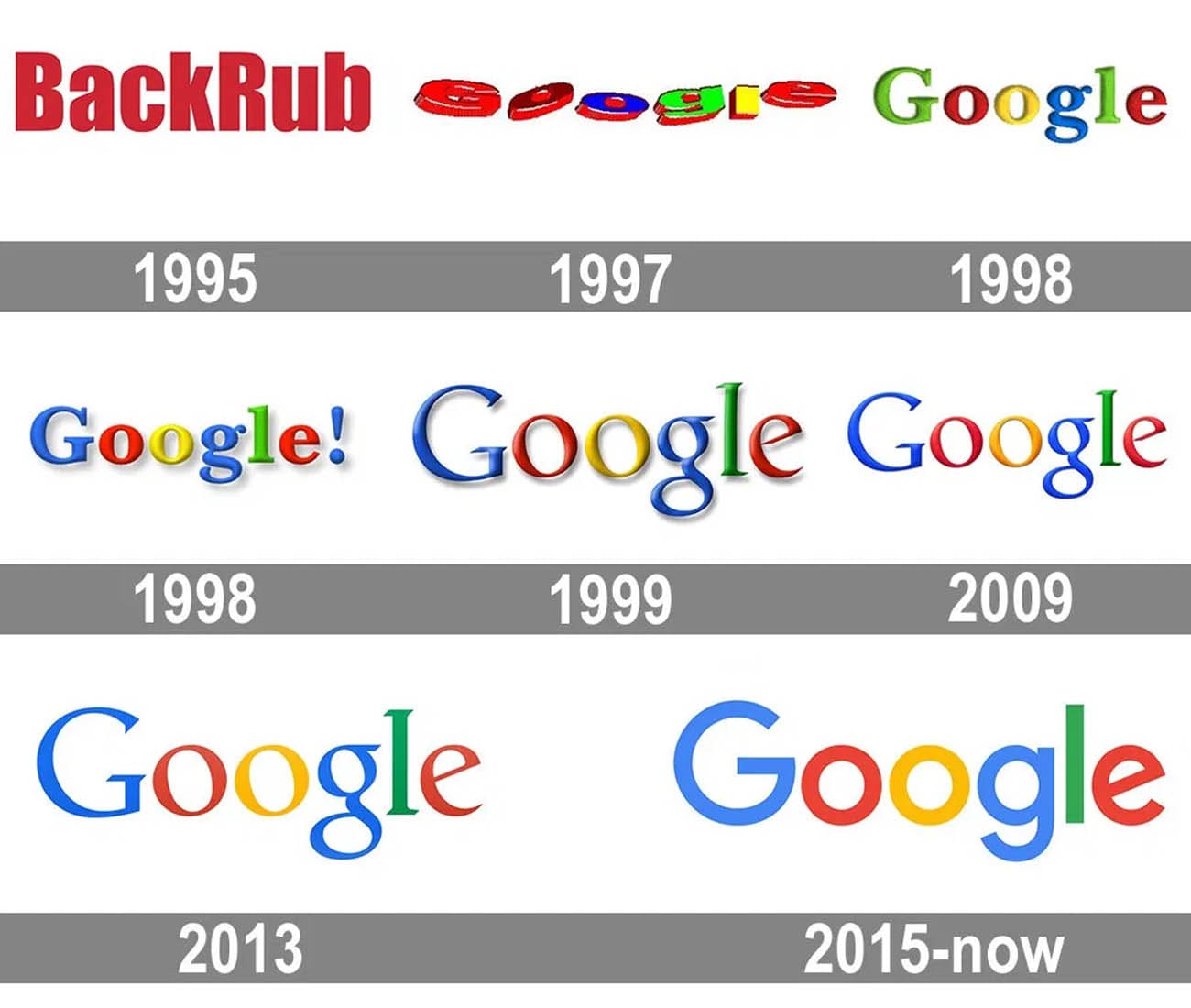

In this chapter, Tufte discusses an unconventional approach to improving fidelity of information design: “add detail to clarify.” This principle challenges the age-old adage of “less is more” which assumes that the effectiveness of a design hinges on its readibility, which in turn means simplicity. Tufte’s argument, however, is not to uncritically cram more information onto a graph - resulting in designs which are confusing and unreadable – but to thoughtfully integrate details into the larger purpose of the design. As he eloquently states in the chapter, micro information “provides a credible refuge where the pace of wisualization is condensed, slowed, and personalized”. The power of micro/macro design is its ability to contextualize the micro reading in the macro reading. He provides a series of examples in the chapter. The first one of which is an intricate drawing of New York City where even the individual windows on the skyscrapers are painstakingly laid out. This design is still recognizable from a distance, hence a macro reading. However, upon closer inspection, personal narratives may be interwoven into the minute details of the visual design – the line of sight from your 23rd floor office window to the St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the feeling of being engulfed as you stand on 49th street past the NBC building. These are all stories which can be read into the micro information of a micro/macro design. He further discusses the infamous Vietnam War Memorial. From a distance a seemingly granite slab with blurred gray etchings, the names of each casualty in the war may be inspected upon a closer look.

This principle introduced by Tufte is especially effective in the realm of map design and can reason why tools such as Google Maps have become so embedded within our digital landscape, deftly interweaving the macro design of maps with micro information.

-

Effective Embeddings of Micro and Macro Designs

In this week’s readings, I’lll be focusing my discussion on Chapter 2 of Edward Tufte’s “Envisioning Information,” which delves into how effective micro and macro designs help to enforce both local/global comparisons. One particularly powerful example I resonated with was the Vietnam Veterans Memorial – having visited it in the past with my family, Tufte effectively put into the words the underlying feelings and sentiments that I had when seeing it for the first time. For example, the memorial is a powerful reflection of leveraging both effective and macro design. From afar, the black granite yields a physical manifestation of what 58,000 soldier deaths equate to, whereas close up, the broad sweeping granite resolves into individual names – with each soldier having a contributing and individual mark. The intentionality of having the downward gradient also aids in the metaphorical meaning, with the names of the dead rising “higher and higher.” Another interesting point Tufte discussed was the notion of how “clutter and confusion are failures of design, not attributes of information.” In a previous reading, one of the questions I asked was whether there was a limit to the number of dimensions that could be effectively mapped. Based on these readings, Tufte would likely argue that no dimension is too hard to map, and that a desire to display multi-faceted complexities is deeply embedded into the social fabric of human connectivity. This can also be seen in Shinkansen graphical time-table, as despite looking extremely convoluted at first, the creators were able to convey the highly complex structure of the railroad system as an aggregate of systemic patterns (as seen upon a close micro viewing).

-

Tufte Chapter 2

I was fascinated by what Tufte writes on page 49: that all the micro/macro designs presented in the chapter so far strained the limits of printing and the threshold of what the human eye registers. One advantage of such boundary-pushing visuals is to make the “information-thick worlds” (50) in which humans live accessible and manageable—or if not manageable, then measurable. Every window in the chapter’s opening New York map example can be visually registered and counted, if one were so inclined. Even someone who looked out at that self-same view from some imagined skyscraper window all their lives could not aggregate the data of windows’ number and position. If visual memory is weak, as Tufte says, then these micro/macro examples present memory condensed, all present at once—and somehow making that vast amount of simultaneous information intuitively readable.

-

Tufte - Chapter 2 Commentary

From our reading this week, I would like to reflect on the design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. At first glance, it’s just a list of soldier names, but the more I understand the concept, the more I love it! It is an excellent example of how to depict micro and macro details. The macro story is manifesting in the massive structure of the memorial. That vast number of names shows the soldiers that this country had lost in a war. The extended design depicts the duration of the war and the chronological order in which these men were lost. As a visitor, walking along the structure reminds us of time and how many soldiers were lost during the duration of the war. For a macro experience, visitors get to read the names of those soldiers, connect with them and relate to the time they lost their lives. I saw many photos of families pointing at the names of their lost ones and connecting with that memorial. It serves as a living structure of the cost of wars, but also, some people feel proud for the sacrifice their loved ones made for their country.

Other aspects that contributed to the macro experience of the memorial are the locations and material used. The site is close to other essential monuments giving this structure significance. In addition to that, the material is shiny and reflective, reflecting the other important structures nearby, making them part of the design. I also feel the reflection of visitors on the stones when mirco reading the list provides a personal experience and connection that is special to each visitor.

-

Tufte Ch. 2

For this reading, Tufte analyzed micro/macro readings and data complexity. I found the examples extremely interesting as Tufte used them to back up his point about complexity not detracting from the design’s legibility.

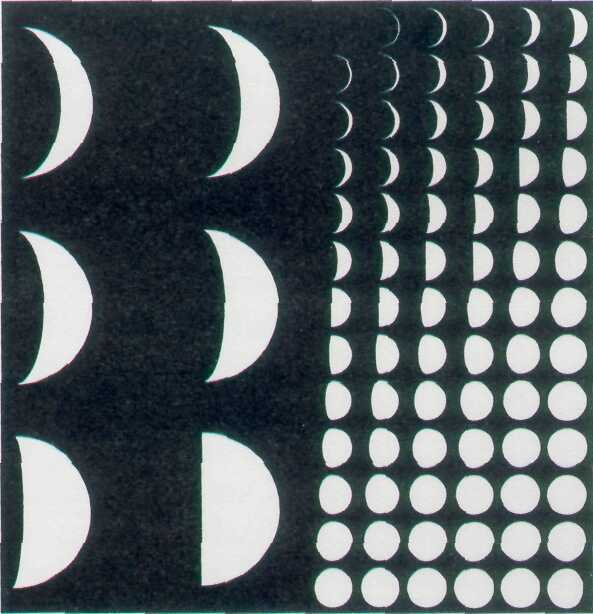

One of the examples I would like to bring up is the Lunar Phase Poster. It depicts an interesting comparison between the boiled down version on the left and the more complex data of the moon’s phases on the right. As Tufte mentioned in the reading, the complex data actually contributes to a better understanding of the moon’s phases. Oftentimes, when we look at data like the simplified moon phases, we lack the full context of information and have to make our own implications. This increases the chance of inaccurate information transmission. The more complex depiction also allows us to clearly see how the moon slowly phases in its different stages. I found it helpful to see multiple small images of the changing moon instead of just six large moon phases. With the six images, I felt it overly generalized the moon phases. Another interesting point to consider though was whether or not the simplified version was more readable to the audience. I agreed with Tufte’s point that “simple” does not immediately mean better readability. In the case of the moon phase example, the simplified version was actually less readable in a sense since I wasn’t able to immediately know what it was trying to convey. However, I think that simplified designs can sometimes be better than complex data displays. It depends on how efficient the complex data is displayed in order for us to have the greatest effect. If used without a clear sense of organization, the loads of data can create clutter, such as the names on the Vietnam War Memorial (if alphabetical, there would be many people with the same names which would be confusing).

-

discrete vs continuous

In this reading, Tufte dives futher into exploring the potential of visual design to transmute the narratives of space and time. What I found to be especially interesting is dichotomy between discrete and continuous conceptions of information. He begins the chapter by discussing the findings of Galileo, wherein discrete observations of stars surrounding Jupiter were docuented. However, despite the intelligence of the astronomers of the time, the leap into constructing a continuous narrative of planetary movement was not pioneered until over a century later. This brings into question the element of tension between discrete and continuous data, and how traversing the axis of these two affects the narratives we tell in information. Tufte further explores a series of train schedules. The first, is a table of discrete information only having information on the arrival and departure of a train between New York and New Haven. He discusses the shortcomings of this design, and presents versions which have improved on this framework of displaying discrete times.

However, a graphical timetable is also presented wherein the train schedule is stretched along the physical geography it traverses, deftly stretching the narrative of train movement into three dimensions.

Questions:

1) In the examples brought up by Tufte (ex. planetary movement, choreography, train timetables), is the use of discrete data or continuous data more effective in “envisioning information” and creating a narrative of space and time?

2) Is having a graphical aspect of design generally helpful for envisioning information? WHen is it not?

-

Tufte Chapter 6 Comments and Questions

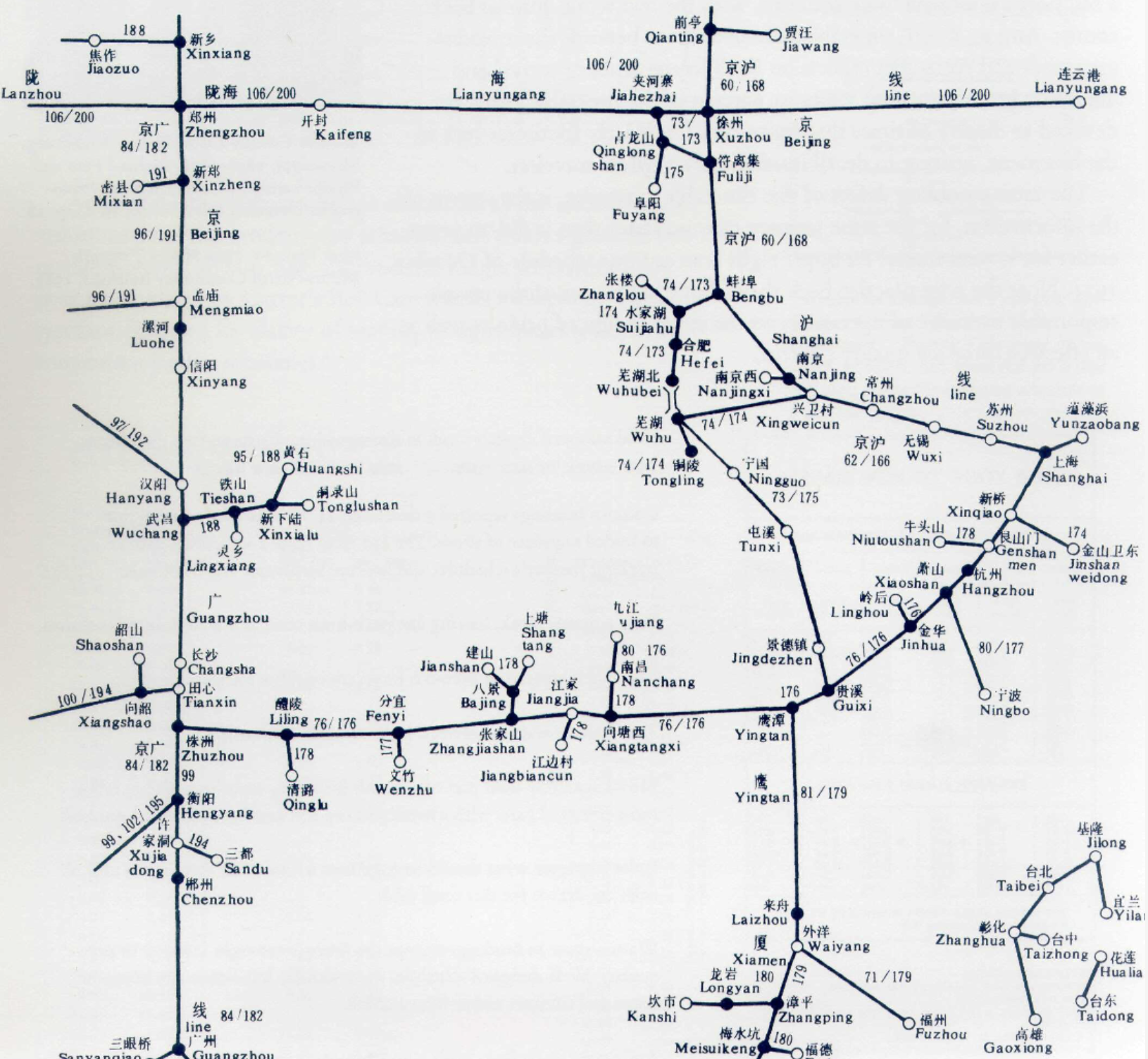

In this reading, Tufte discusses how space interacts with time, using particular examples of various transportation schedules. It is interesting how Tufte uses timetable design to illustrate his points about envisioning data, but it makes a lot of sense to use the example of timetable design given how timetables usually include large amounts of dense numerical and spatial data and figuring out how to organize the data for a general audience. I was really surprised by the design of the 200-page timetable for the railroads of China—particular to the designer’s dedication to maintaining the full spatial relationships of the towns. Looking just one page at a time at a section of the railroad routes, the lines that connect various stops make the map seem very clearly organized and it appears helpful to have the distance between each stop actually reflect the real distances in China.

Questions:

However, I wonder if we consider the general every day user of a train timetable in China

1) Is this dedication to preserving the spatial relationship/directions actually helpful for navigation (since train riders probably care more about the number of stops than the exact direction and distance between stops)?

2) This also brings about the question about the tradeoffs for when is it worth it to accurately display the spatial relationships (eg. using 200 pages to illustrate the railroads with very fine accuracy) vs. when is it okay create a design that gets the overall point across for time/space relationships without being very granular?

-

Tufte - Chapter 6 Commentary

I was most interested by the narrative aspect of depicting time; from Galileo’s moons to the graphical train schedules, each diagram tells a story about the intended or normal operation of movement over time. In “flatland,” all moments are simultaneous—all continuous and reliant on the previous moment’s accuracy. (Obviously more true for planes and trains than, say, moons…) How does narrative storytelling enhance the authority of these designs? The “visual instant” as Tufte calls it includes many normative assumptions, most strikingly to me in the example of the dance step diagram: prescritpions of correct movement and timing are present, but so are prescriptions for dress, for the gender presentation of the two partners, of how to wear your hair and hold your body. Clearly many of those prescriptions are outdated, but it made me wonder, what other subtle prescriptions and ideologies are baked into graphical representations of time? Or instance, the efficiency and expedience of the train schedule prescribes that one should move between metropolitan areas, rather than any other kind, and move with the greatest speed possible toward another urban center, thus establishing priorities of time and emphasizing cities as areas of activity and movement.

-

Tufte Ch. 6 Comments

In this reading, Tufte discusses space and time. From this chapter, I gained a few new insights about the time/space relationship. Tufte presented various examples of designs where movement over time was expressed. This showed how space and time can be depicted in such different ways: either segmented out in a grid time table, continuous movement of a line, and abstract zigzagging and representations of movement steps. Movement becomes an abstract concept that can be translated from the 3-dimensional world to the flatland design while maintaining the transitions over space and time. Another interesting thing I noticed was how the depictions often had to visualize something that we do not necessarily see in the same way normally. For example, in the dance notations, the figures are limited in their space. They are frozen as an illustration, but simultaneously, they are used to show something that translates over time. The lines in the drawing on the “floor” track the dancer’s movement, but it is a different visualisation than we normally see in real life. While we see a dancer’s body lines and shapes in the 3D world, the notation diagram breaks it down into a series of lines and symbols.

Questions:

-

How must designers consider balancing accurate depiction of movement versus visual aesthetic? For example, in the New York to New Haven timetable, there is a difficult balance between being straightforward to viewers while also avoiding ambiguities.

-

How are symbols integrated into the designs to fully convey space and time (like movement)? What leads designers to use these symbols and how do we ensure that the viewer understands it? I found it appealing to look at the dance notations, but it would require more information for me to fully understand it.

-

-

Exploring Narratives of Space and Time

This reading on Tufte discussing narratives of space and time, and I found it particularly useful for clarifying how to work with them as graphical dimensions and providing various examples of interesting ways of using them. Because it was the most applicable graphical combination, Tufte focuses a lot on timetables, which are interesting because they are so ubiquitous they are almost taken for granted. Yet, by comparing many different ones, we can see that a lot of them ignore or collapse space, often to the detriment of the visual appeal. Tufte picks apart an overcomplicated timetable, and the side by side clarity with the better designed version makes it clear that good design can help untangle these dimensions. I think the most interesting timetables examined were some of the ones that didn’t collapse space, and instead depicted time on one axis and space on another. These maps of space-time are really cool conceptually, and I feel like they offer a lot to explore in terms of design spaces, so I’m excited to think more about them and potentially utilize their ideas in our final project.

Questions

- Do visual representations of things like time fundamentally help viewers think about the information differently? Would a different set of metaphors or starting concepts applied in creating a visualization lead to a change in the way the viewer thinks about it?

- Are there new ways to encode more information into the same amount of space? Is this a thing that technology or culture can improve on or is it inherent to the brain?

-

Applications in the Narratives of Space and Time

In this week’s discussion, I’ll be talking about Chapter 6 of Tufte’s Envisioning Information, focused on the narratives of space and time. One of the more intriguing elements of this chapter was on the discussion of how certain design elements can contribute to an effective or not effective timetable. For example, Tufte hones in on the challenge of developing these timetables – given that they contain large arrays of “fussily annotated numbers, thick information densities, type and image together, and multivariate techniques for narrating what is a four or five variable story.” As a result, there is a dire need to provide an intuitive and self-interpretable format as seen with the China Railroad Timetable and Czechoslovakia Air Transport Company Schedule. Both of these designs use a simple arrangement of circles and lines to deconvulute a mass array of information. In contrast, the New York to New Haven Timetable serves as a negative example of timetables, with a lack of purpose in the distribution of space and efficiency in the display of information. This goes to show that even data that isn’t “chartjunk” needs to be displayed properly, and utilize principles rooted in design and dimensionality reduction. Two additional questions I had from the readings are 1) The author mentions the power of having “the same picture, but many stories.” How do we strike a proper balance between having a clear cut and guided narrative itinerary without offering too much room for interpretation (to the point that it detracts from the desired underlying message). 2) Is there an upper bound to the number of dimensions that can be effectively reduced and convey in a time-table? It seems that as the number of dimensions increases, the barrier to understanding also tends to increase proportionally.

-

Questions from Tufte's Chapter 6

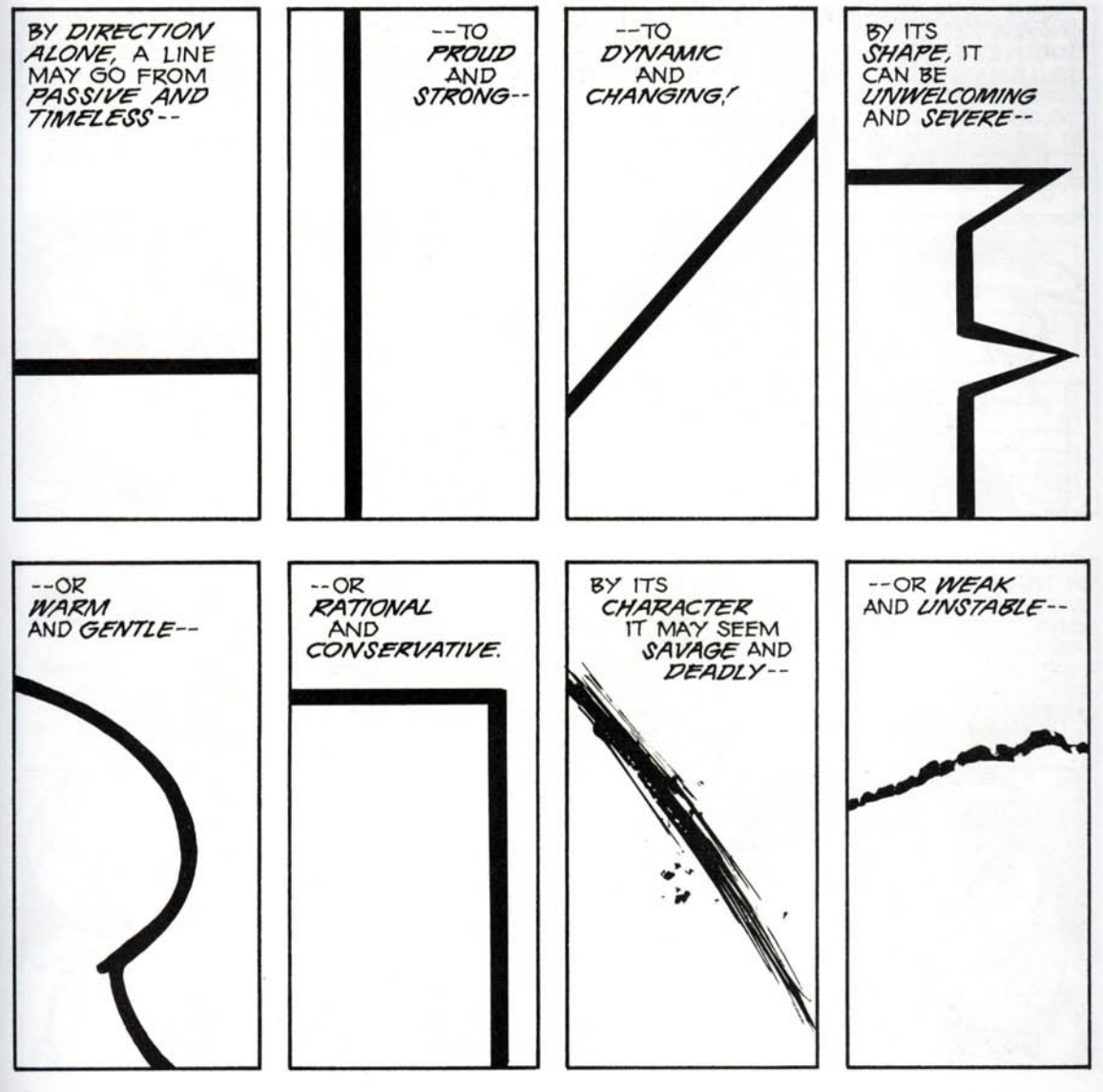

What elements learned from Dondis techniques for visual communication make dance notation so effective and in what ways do they aid in the representation of space and time? (Depth, activeness, symmetry, balance, etc.)

How do we go beyond representing a range of motion to representing a specific trajectory in a static image? In other words, how can we clarify direction and/or start and finish?

-

Narratives of space and time - more is more?

In Chapter 6 of Envisioning Information, Tufte gives many examples to show how movement can be represented in the flatland. The corkscrew diagrams of Jupiter’s satellites provide much more information than a column of Galileo’s discrete illustrations of the satellite positions, since the satellites are constantly moving, so it makes sense that their movements would trace a continuous line. I found the redesign of the New York/New Haven train schedule extremely informative and really demonstrated how design elements can make data more easily digestible. Tufte points out each specific design failure in the original timetable, and corrects them in the redesign. What other elements of visual communication from Dondis could we apply to the timetable to make it even more effective?

I thought it was very interesting that sometimes showing just a little more information can make it easier to understand a graph, such as the example of the Chicago/Atlanta airplane schedule, in which the two edges of the graph overlap in time, so that the viewer can see a complete day of travel no matter when they begin. It makes me wonder why there are not more maps that repeat elements to show each country in its entirety.. maybe because most maps are extremely eurocentric. It was also interesting that sometimes making information too dense to decipher can be a useful design choice, such as in the example of the Hoboken/New York bus schedule, where lines that are too close to distinguish tell the viewer that the bus is extremely frequent and that they need not worry about the exact times the bus arrives or departs.

Personally, I found the graphical representations of dance movements all quite difficult to understand, probably because it is so hard to document all the possible ways the body can move and I was overwhelmed by the amount of graph-specific notation to remember. I think that dance movements and routines can potentially be effectively represented in conjunction with music by 3D models (either physically or digitally), but I wonder if there is an optimal and not cumbersome way to show dance and music together in the 2D space.

-

Tufte's Color and Information

In Tufte’s “Color and Information”, he highlights a few rules for good practices in design all revolving around the use of color. These rules focus on conveying information in a way that is effective and easy for the reader to comprehend and find visually pleasant. One of the quotes that stood out to me during the reading was “so much visual excitement, so little data” when describing ineffective/excessive color usage, ehich is exactly what we want to avoid.

I never really though about the effectiveness of grey backgrounds, but when thinking of Tufte’s first and third rule of using bright colors with dull background tones (as opposed to having multiple bright colors next to each other clashing) I realized that it produces really effective results by conveying only the data that is important. The second rule also relates to this in terms of how separating bright colors with white only makes the contrast worse by emphasizing their contrast.

All of Tufte’s rules seem to relate back to visual cohesion. For example, the fourth rule communicates how having large enclosed areas of two different colors breaks up the image. However, if these different colors are intermixed, the message does not get lost. This goes hand in hand with the use of gradients and value scales, especially in maps.

-

Tufte Chapter 5 Color and Information

Reading Tufte’s chapter on “Color and Information”, I think Tufte makes a really interesting point when he lists the two requirements which would make using multiple signals effective (ie. the need for it and the appropriate choice of design technique). This framework for deciding when to use multiple signals to encode the same information would be really helpful to apply to our own designs, not just for mapmaking. Just looking at the examples, it seems like the strategy of multiple signals can create a really sturdy design/communication but at the same time has the potential to go too far and clutter the design space. These ideas reminded me of the Spiekerman reading on typography. Similar to how it is helpful to use different types in order to convey different meanings or personalities but to keep in mind that too many different types can be visually confusing, too many different colors and signals may work to communicate more ineffectively. Additionally, when Tufte discusses Byrne’s colors in “Elements of Euclid”, especially when he talks about using 4 colors that provide maximum differentiation, it also reminded me of the Spiekerman reading and readers were able to match different fonts with different shoes/personalities.

-

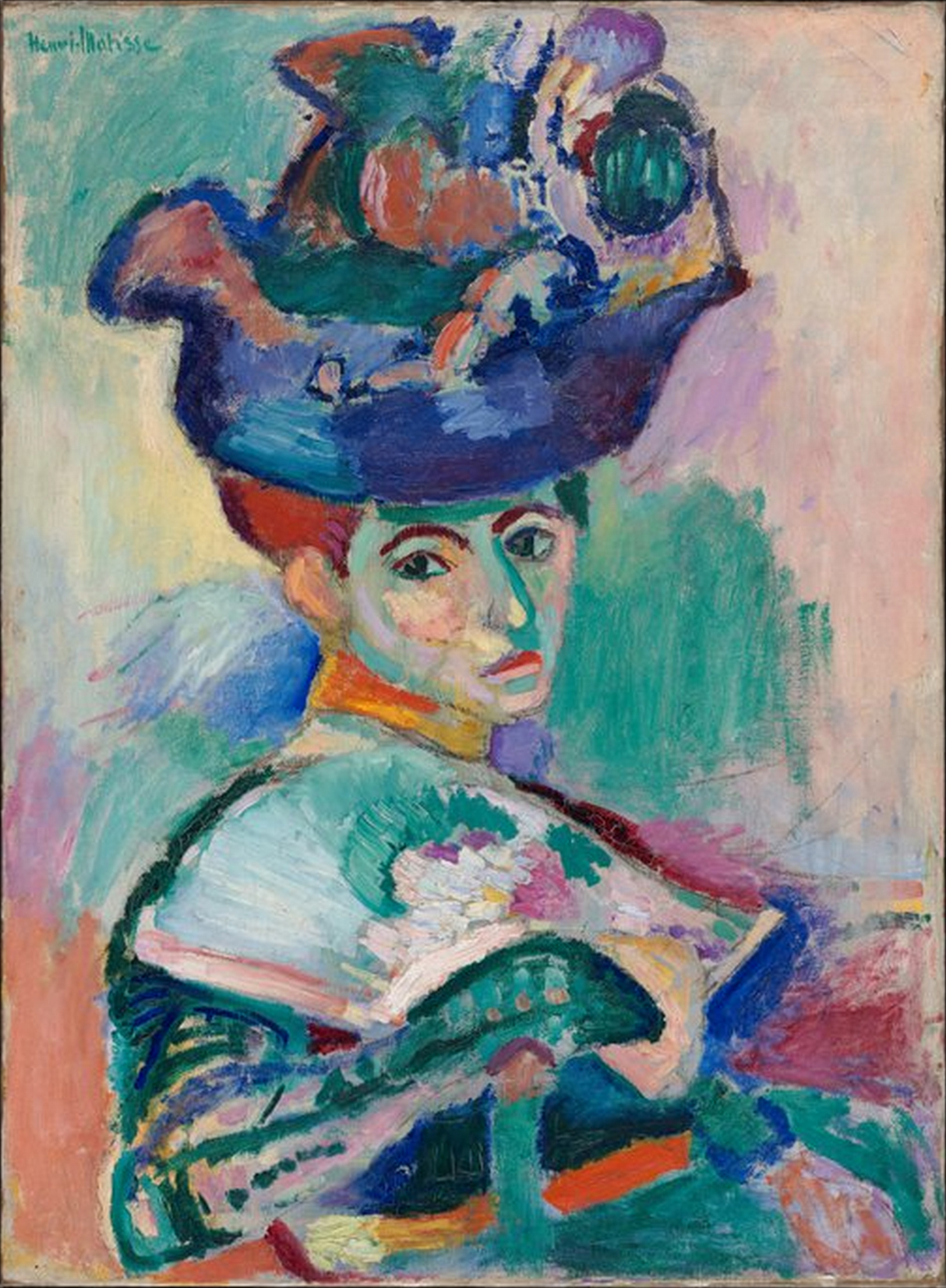

Tufte and Color

I love the idea that Tufte puts forward at the beginning of this chapter about color as measurement—that something about the intuitive human sensitivity to color allows us to use it as a system of measurement. Rather than dealing in simply color-coded absolutes, like in Burnham’s simple map on pg. 4. Although I’m not consciously aware of the hue, saturation, and value inherent in every color I see, the contrast between two different shades of blue or intensities of the same blue has an immediate, tactile effect. Tufte uses the word “enliven” to describe colors’ effect, and I think that’s as good a word as I can think of: there is a living, dynamic sense to the intuitive understanding of color that can support and enhance more “flat” data.

-

Color & Information Tufte Ch. 5 Commentary

In this excerpt from Tufte, we explore the different uses of color and how it holds information. It was interesting to learn about how best practices evolved based on the effectiveness of the design. Many of the best practices seemed to center around the idea of making something easy to process and creating a sense of balance. Examples like William Henry Toms after Thomas Badeslade, Chorographia Britannica or, A Set of Maps of all the Counties in England and Wales . . . (London, 1742), plate 18 and Thomas Badeslade, A Compleat sett of Mapps of England and Wales in General, and of each County in particular . . . (1724), pen and ink, and watercolor on vellum, leaf 35 (recto) contrasts various practices and highlights the development of effective color use and theory. In a way, this reading reflects our past reading by Dondis where color was discussed as something that could carry meaning and represented something. In the examples here, color is a carrier of information and depending on its application to the design, it can make it easier or harder for the audience to process the information. It was also interesting to explore the criteria of failure when using color, where generally, if colors overwhelm each other, it is a failure. Tufte discussed the importance of context for color as the way we view a color changes with its surroundings.

-

Tufte Ch. 5 Commentary

In this week’s reading, Tufte talked about color and multidimensionality. This relates directly to our Dondis reading. They both emphasized how color is a practical element in visual design to portray more dimensions to objects, paintings, or data. Tufte supports this by providing an example of a scatter plot with clusters of different colors. Without the colors on that flat plane, we couldn’t have noticed the groups the emerged in the dataset. Another aspect of color is the variations it provides through the different hues and tones. However, according to Tufte, this is not an effective tool used alone. He suggested using other cues in addition to colors such as size or shape to make the variations more visually powerful and precise.

-

Color Context

One point Tufte makes that stands out is arranging colors so they trick the eye. In his example of a brownish square looking like deep gray due to it’s proximity to white, he highlights just how easily color can trick us into seeing or missing details. On the flipside, the same color can look extremelty different or carry different meaning based on its surroundings (as seen withh the blue squares). This resonates because it’s easy to think of changes in color or hues as isolated. However, depending on the surroundings or context of that color, it can vary in its delivery of information. The “harmony” of the main color of an image can altered by the context it’s been placed in.

This gif reveals just how defining a color’s surroundings are. Despite the two stars being identical, they look very different from one another. This is important because in application, the designer must not abstract colors out of their design but think about the entire piece’s color unity. Tufte mentions screen vs. paper. The same pink star on a stark white background versus a pink star on a toned-down screen background may bring different meanings to a viewer. Thus, we need to take context of the design’s color into consideration.

-

Fundamental Uses of Color in Information Design

In this week’s discussion, I’ll be discussing Chapter 5 in Tufte’s Envisioning Information. In particular, he focuses on the fundamental uses of color in information design and how it can aid or sometimes detract from the aims of a piece. For instance, one particular example that stood out to me was the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, which conveys ocean depths and land heights in 21 steps. Rather than making a statement about the color solely, it serves as a clear statement about the geography with every color mark serving a purpose (ie. to communicate attitude, longitude sea or land, and depth or altitude). This resonates the central principles found in the Dondis readings, where color has the ability to “separate worth informationally through symbolically attached meaning.” Interestingly, Dondis also focuses on how colors have a strong emotional affinity for each individual, and I’m curious whether Tufte would consider these emotions to detract from the aims of a piece aimed at conveying very logos-focused pieces. On the flip side, Tufte also points out how color in the wrong context can result in a “failure” for design. For example, he cites Oliver Byrne’s 1847 edition of Euclid’s Geometry, which he argues the reader spends too much time “puzzling over an alphabetic macaroni of 63 encoded links” between diagram and proof. This points toward a broader discussion of properly conveying one’s desired goal when incorporating both text and images, which is what we saw in Chapter 6 of the McCloud readings. McCloud focused on categorizing how to best incorporate text and image, and how an additive combination approach can better serve to amplify the desired message (rather than in Byrne’s case, where the texts and mathematical symbols fail to synergize). Finally, I also found Edward Imhof’s discussion particularly interesting, with regard to the 4 rules governing the role color plays in cartographic science. It echoes much of what we found in Dondis’ visualizing information where form is very much affected by content and content is affected by form. It also raises the question of how universal his rules are, and whether there is a certain degree of interpretation or subjectivity involved?

-

color and information

In this reading, Tufte incisively discusses the capacity for thoughtful use of color to effectively capture information in design. Similar to Dondis’s analysis, Tufte describes how color choice impacts the overall message of a design, however, does not delve into the intricacies of Dondis where they describe the effect of changes in hue, saturation, brightness, etc. Rather, the core of Tufte’s argument is that, “The fundamental uses of color in information design (are): to label, to measure, to represent or imitate reality, to enliven or decorate.” He structures the chapter by going through principles established by Eduard Imhob in Cartographic Relief Presentation. The first two principles discuss the minimization of color damage by avoiding color clutter, where bright and light colors are placed closely adjacent to each other. The use of loud colors overwhelms the viewer and adds noise to the design, harming it’s ability to effectively communicate with the audience. Tufte points out that the use of primary colors with neutral colors is therefore especially effective as they provide maximum differentiation. The third principle describe the use gray in design as it is “the prettiest and most versatile of colors” highlighting brighter colors and consequently highlighting information.

-

Color and Information Best Practices

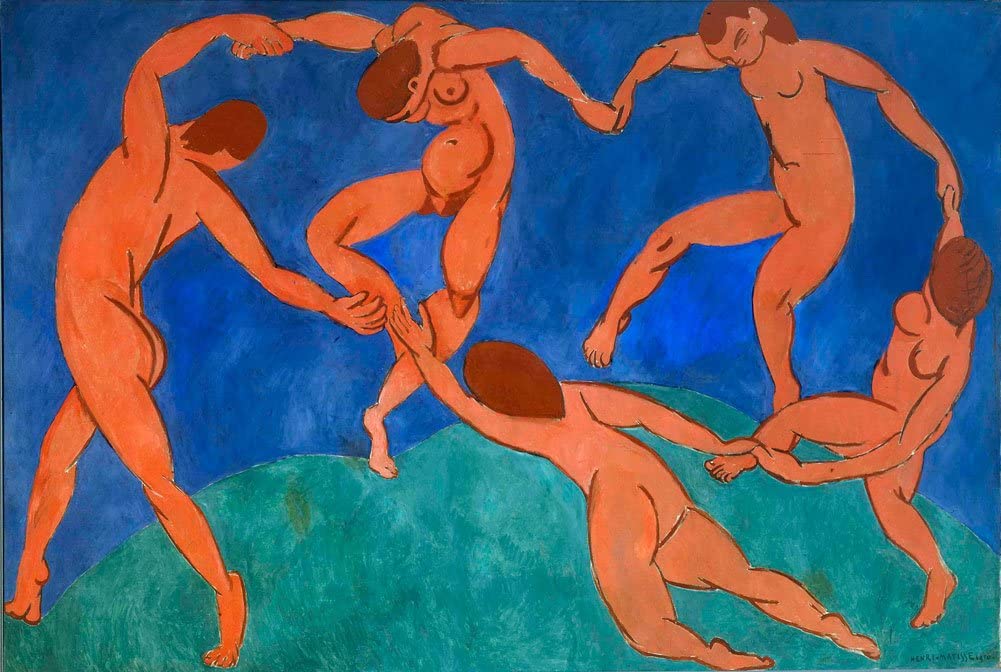

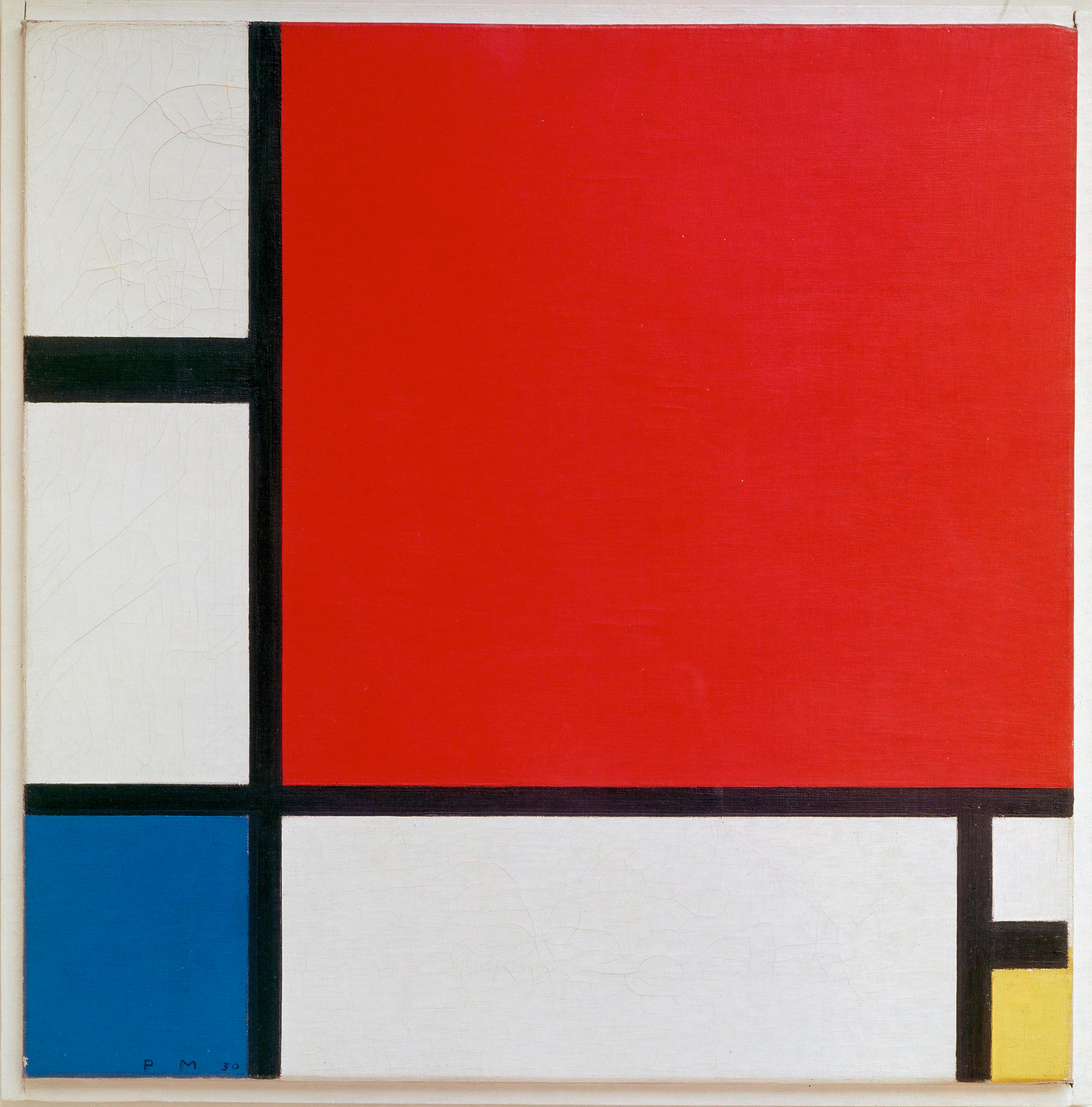

In the Dondis readings, he laid out the fundamental elements of visual design, of which color was one of many. One of the issues that Tufte addresses is that often, color is added to data visualizations for its own sake rather than having a specific purpose which obfuscates the data. As with the notion of chartjunk in other manners, I enjoy Tufte’s ideal of purpose behind all visual aspects, including the choice of color and inclusion of color itself. I also think the focus on contrast was important and pairs well with Dondis’s comments on it, as without thinking about how the colors play off of each other, a whole piece can be noisy or jarring. While there are many different ways to make a successful piece, there are just as many ways to fail, such as by picking colors or a palette that are jarring when next to each other, or by not having enough contrast when color-coding, which can make it hard to extract information from a piece. In terms of artistic background, I enjoyed the comparison to Mondrian pieces, but I think there is inspiration to be drawn from many different art movements, some with more radical choices in color and shape that could still be made pleasing to the eye. While I think nearly all of Tufte’s advice is good, one drawback I see is that a lot of his advice is very prescriptivist, which homogenizes the work of the designers who follow him. While this may result in well-crafted pieces, it also makes them less interesting than those who try something new and are constantly pushing the boundaries.

-

Envisioning Information

In chapter 1 of Envisioning Information, Tufte describes the challenges of representing multi-dimensional (more than 3 dimensions) information in a “flatland” or 2D space. Some strategies he provides for making this task easier include using symbols/icons to compress more data, and including multiple dimensions of data along a single axis in the 2D space. The strategy that Tufte focuses most on in chapter 1 is that of small multiples, which uses repeating design structures to provide another dimension of information and encourages local comparisons. Tufte writes, “this constancy of design allows viewers to focus on changes in information rather than changes in graphical composition.” I think the graph of air pollution in california conveys idea of small multiples the best because it doesn’t have too many multiples, so it is not overwhelming, and it is also easier to see the differences across time periods because the individual graphs are relatively close together and can be viewed all together.

-

Tufte - Chapter 1

Tufte’s first chapter was deeply instructive in how many dimensions and data points can be organized and represented via the two-dimensional medium of a graphic or map. The example that stood out to me as most jarring was the map of air pollution; I think part of the reason for that was the map-like nature of the graphic and the automatic—or at least initial—reading of the conical structures as shapes in the landscape. Of course, reading the caption, that question’s cleared up and I can recognize the various axes of the graph and understand it as reflecting pollution levels, rather than graphical depictions of land. But it was interesting to me how closely the two graphic strategies appear and how different the data is that they represent. My first impression was of the representation of something physically and perceptibly occupying space, which is not true: what’s represented is in the graphic is nothing that human perception can reproduce, unlike recognizing the contours of a map. Data transformed in this way from imperceivable to scalable seems far more intriguing to me even than the sunspots example. In the case of the pollution graph, the imperceptible is made into an entirely new form that feels intuitive on first glance.

-

Tufte Chapter 1 Comments

Tufte gives a lot of interesting insight in how to represent multiple dimensions of data on a flat 2-D medium. One of the examples that I found very successful in conveying multiple dimensions of data are the graphs of three air pollutant in southern California. The use of small multiples was very effective because once I understood one design, since the structure was repeated for the other images, I got a sense of familiarity and easily was able to comprehend the other images, which gave even more information on the time of day in which the air pollution is happening. Also, I really like the representation of space and amount of pollutant in this map, as it makes it pretty clear by the heights and locations of the bars where the concentration of pollutant is and how high it is.

One example that Tufte used to describe why chartjunk is generally undesirable was the “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” graph. I agree that the chart has design beyond the bare minimum, however I still think this chart is effective. I can very easily see the trend of the data and the stylistic choices of the graph and the image of the woman makes the data very memorable and I appreciate the creativity to connect how data looks to real world scenarios. I personally think that Tufte might be overly emphasizing the need for charts and graphs to be high information and show a high density of data. For example, I think it’s actually really difficult to determine trends in the japanese weather chart and that there is almost an information overload. Depending on the use case, I think preparing the data and taking averages or doing other kinds of transformation is wise to do before trying to communicate every single point of data to a viewer.

-

Escaping Flatland Commentary

Tufte presents the different approaches to using flatland visualizations through various examples. One of the examples that first caught my attention was Kellom Tomlinson’s “The Art of Dancing”. This example used realistic perspective to extend out of the bounds of flatland design. However, it also mixed in multiple depictions of movement: one way was the anatomical movement of the figures themselves and the other was the line path of where the figures were going to move. I think this was one of the successes of this particular design since it adds dimensionality to a static, flat medium. I did find that the information carried by this design was slightly unclear though since the lines on the floor can be interpreted as scribbles. This design expects the viewer to understand the visual representation when in fact, it seems somewhat ambiguous without additional information.

Another example that was interesting was “Color Coordination”, redrawn from Yumi Takahashi and Ikuyo Shibukawa. Here, colors were used as supplemental visual information, differentiating the shirts from each other. Although three-dimension isn’t used in this design, the uniformity of shape and differences in color create an attractive design. This also allows the viewer to easily scan through the overall design and to attach onto the only difference: color.

-

EE Tufte

Two main points from this reading greatly inspire me: turning natural science into 2D and repetition to draw one’s eye in. From the planetary allignment to sunspots to carbon monoxide readers, this piece delves into effective ways science can be depicted. With the solar system, the 2D image reveals the gears and technology all in one straight line. This allows readers to see every planet in the system without becoming confused due to the convolution of multiple moving parts. Crucially, this draws me in because I want to imagine the planets circling each other and the gears turning, but I can picture it because of the simplicity of the drawing. To the author’s point, however, the original meaning of the work does get lost. Rather than focusing on the planetary interaction, this piece brings my attention to the incredible machination.

With repetition, whether it’s sunspots all in a line, varrying colored t-shirts all together, or a comparison of celebrities wearing the same outfit in a magazine, repetition effectively draws attention as well. It reminisces childhood games of “spot the difference” while also being satisfying to the eye. Drake recently used this technique with his album art: the same emoji in different colors alligned in a grid form. These small multiples give us much to observe without forcing us to scroll or flip tthrough pages.

-

Dimensionality and Chartjunk

The Java railroad line example Tufte brings up is one of the most dense visualizations I’ve ever seen. While it’s far too complex for the average person to use, it accomplishes its goal by compressing a lot of data into a visualization that can be understood along multiple axes and used for multiple purposes. Tufte’s focus on dimensions is a good framework, because fundamentally all complex visualizations have to figure out how to map their axes, and showing complex graphs gives examples of alternative structures to do this. I also think this graph specifically is a good example of the idea that a designer must design for a specific audience, as if the designer was sticking to the conventions used for informing the public, they may have simplified too much. The designer used every bit of available space, and this may have been made even more important due to the fact that this was classified document that may have been needed to be transported often. This stands in sharp contrast to the chartjunk that Tufte refers to, which adds extraneous detail and space. While these ornamental things may seem fun, they distract the viewer from the content and often can even obfuscate the data.

-

Chartjunk or Art?

Tufte gave valuable insights into how designers can escape the limitations of flat displays. He shared examples of data stories that expressed multiple dimensions on a simple plane, such as newspapers or reports. My favorite example is the criminal activity chart supplied by counsel. I am not sure if I want to call this a chart, though, as it is a table. Tables are the best representation of data with multiple dimensions and could give so much information in just one glance. They also invite users to read them horizontally and vertically. However, one problem with tables is scale. When there are multiple rows, there is a need for aggregate views that are provided through other types of charts such as bar or pie charts.

There is one point that I can’t entirely agree with Tufte about. It’s his strong position against “chartjunk”. To the author, adding irrelevant visuals to charts that do not represent data is distracting and disrespectful to viewers. He gave an example of the “Diamond were a girls best fired chart”. To be honest, it was one of my favorite charts in that chapter! I loved the story, the play with curves, and the title! I feel it is disrespectful to call such effort “junk!” Data stories are visual, and it’s wise to blend in different representations. One side represents the data, and the other side is representative of the context or culture. This makes the design space much more creative and enjoyable!

-

An Escape from Flatland

In today’s discussion, I’ll be focusing on Chapter 1 from Edward Tufte’s “Flatland,” in which he identifies how all communication between the reader and makers of an image must be conveyed on a 2D surface - thus necessitating the escape from “flatland.” One particular example that struck me was the graphic timetable for a Java railroad line (Soerabaja-Djokakarta). In contrast to typical railroad maps which are very simply laid out, this graphical timetable is able to convert the three spatial dimensions of our daily world into one train relevant dimension. Upon first interpretation, I was easily lost by the complexity of the data presented, however it soon became a puzzle to figure out what parts corresponded to what. I found this especially captivating, for example, where the left margin of the timepoint represents a profile of the valleys and mountains crossed by the rail. This subtle detail provides a further nuance that isn’t captured in conventional maps, and epitomizes how the complexity of a 3-dimensional space can be converted effectively onto a 2D “flatland.” The design also suits the function, as this “16 variable schedule served as an internal planning document for the Java Railroad.” On the other hand, Tufte also identifies how the lack of these design principles can serve as the downfall for “chart junk” labelled pieces. For example, he points out Peter Blake’s “God’s Own Junkyard,” in which a whole building was distorted into a duck. Rather than having the work be open to self interpretation, this piece instead seeks to attract and divert attention by means of “display apparatus and ornament.” These negative features are factors that I will definitely be attune to for the future projects such as the mapping experiences project.

-

Viviana Envisioning Information

The example from the Envisioning Information reading that stood out to me the most as interesting and effective was “The Art of Dancing” because it incorporates many of the elements we have been talking about that add depth to a design. For example, the shadowed floor breaks away from the 2D flatness of a page and adds perspective and angle. The symmetry between the dancers created tension and draws you into the center of the page. Additionally, the representation of music, movement, and dance on the floor through overlapping and smooth curved lines adds fluidity, airiness, and movement. All of these elements help the design to “escape flatland” and achieve a more realistic and profound message.

A not-so-successful example that also stood out to me was the “chartjunk”. Where Tufte says “Cosmetic decoration, which frequently distorts the data, will never salvage an underlying lack of content.” Which deprioritizes the data in exchange for a cliche image that does not contribute to the content of the design. The information is unclear, hard to read, and clearly not the main focus.

-

Although the trends of of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization are used by van Leeuwen and Djonov to explain kinetic typography, the concepts of these four trends have all been described in various chapters of Mccloud’s Understanding Comics that we have read before. Although not explicitly described using the same terms, chapter 2 of Understanding Comics explains how symbols convey more meaning visually than plain text, just like how pictorialization in kinetic typography can convey more meaning about the word or phrase. McCloud uses the Big Triangle of reality, meaning, and the picture plane to place symbols and pictorialization in the center, between meaning and reality. In chapter 6 of Understanding Comics, McCloud explains the progression over time of writing towards a more colloquial style, which can also be described as informalization. In a similar way, this informalization can also be represented as moving from the reality and meaning corners of McCloud’s Big Triangle towards the center. Emotivization brings us back to chapter 5 of Understanding Comics, in which McCloud shows how visual elements can convey emotion without telling us and explains the expressionist art movement when artists wanted to convey feelings through their work that can’t be seen in real life. The connection between van Leeuwen and Djonov’s trend of dynamicization and McCloud’s Understanding Comics is not as clear as the other three, but McCloud does always seem to cover how people naturally progress towards movement and change over time, in search of a way to convey more meaning without losing too much of reality, towards the center of the Big Triangle.

-

Semiotics of Kinetic Typography

The ideas of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization relate to other concepts we’ve explored in other readings. I found that pictorialization reminded me of the Cohn reading because the examples of the word “circular” going around in a circle shape or the word “help” vibrating to convey a sense of fear reminds me of conceptual metaphors. Specifically, the “circular” example is reminiscent of the english idiom of “going around in circles” and the “help” example is related to the english phrase of “trembling with fear”. Both examples seem to rely on familiarity with these phrases + external context.

Emotivization seems to be related to the Spiekermann reading, especially the part where he gives readers the opportunity to experience different typographies by changing the color of the reading’s type, or when it became light on dark type, or when the type changed dramatically. This experience helped me to understand more deeply how typeface changes what kinds of emotions and how messages are communicated. Additionally, the reading talked about how certain typefaces are instantly recognizable and association with a brand or activity, so this association could bring about instant nostalgia or connection to a certain emotion one might have about a brand/activity.

Informalization calls back to many of the concepts that Mccloud covered in the chapter where he presented the framework with Picture and Words on either side of a balance beam. Whether in comics or another area of design that involves both picture and words, the balance words and pictures as well as how they interact and work together really affect what information is being conveyed. For example, the connection between the words and an image in a comic might be critical to understanding how a character is really feeling + the nuances. Dynamicization reminded me of the NYTimes article about Durer for some reason. Perhaps it was because this week’s reading talked about how cultural trends contributed to the “cultural preparation” of kinetic typography. And I thought of how self-portraiture has a long history and it kind of primed our generation/culture for the concept of a “selfie”.

This grammar of kinetic design and dictionary of common kinetic typography concepts seems open up many avenues of creative new ideas that designers did not have access to before when either the designers were stuck thinking statically or when the audience didn’t have the proper visual vocabulary and familiarity with non-static designs. However, I think this grammar and dictionary might result in constraints due to software systems that make design possible having a lag since people can always be creating new ideas or concepts, but then the software has to be updated with new features that allow additions to the rules + grammar.

-

Kinetic Typography

Semiotics of Kinetic Typography bridges what we’ve been working towards with nuggets of knowledge we’ve learned along the way. Pictorialization strongly connects with Spiekerman’s discussion of typeface. He made the point that a “Y” can mirror someone with their arms outstretched with joy. Although that’s not what “Y” repesents always, that similarity (and design idea) demonstrates how pictorialization can add greater meaning to information (words). Along that line, there is also a large connection between pictorialization and McCloud’s point on text and visuals working together. Individually, we have an idea of rope and what “Ahoy” means. However, when the two are combined, they form a fun look and convey more meaning than when they are separate.

In some ways, Informalization mirrors the vagueness achieved through simple comic characters. In the comics, the character is left less filled in than their surroundings so we can put ourselves in their shoes. With informalization, the words used are less complex so we can empathize with the host; we think of them as our personal friend. In both instances, reader or listener is given room to project their own feelings and sense of self into a situation. Emotivisation elaborates on this connection by enhancing feelings throughh visuals. To Spiekerman’s point, by changing the color and thickness of a typeface, we convey deeper meaning like joy or anger or hesitation. Dynamicization gets at what we hope to accomplish with our projects. By enhancing the movement, we strive to capture our reader’s attention. After we’ve drawn their notice, the movement will hhopefully add to our poem’s meaning.

By utilizing this “grammar,” we can utilize ideas about how movement currently connects with verbs in order to enhance our own animation. By using prior-made rules, but inserting our own movement, we’re able to capitalize on finding the middle ground with something that looks fresh.

-

Kinetic Typography Comments

The concepts of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization are intertwined with past concepts that we have read about in various ways. Pictorialization seems to relate to one of our McCloud readings where we explored the connections between text and images. It was interesting to see how the text itself could become imagery in a way and convey something to the audience. Informalization reaches more to the audience to create associations and take context in order to understand the full meaning. Emotivization leads to creating an environment for the audience and conveying something more than meaning. It becomes a feeling. These ideas were also reflected in the Spiekermann reading, where fonts were analyzed on what they can portray. Dynamicization provides change and movement to type, becoming a part of visual information that we absorb.

A grammar of kinetic design allows type to become something beyond just the meaning of the word/s. By using kinetic typography, more information can be translated to the viewer and certain meanings that cannot be relayed through words becomes accessible.

-

kinetic design

This paper discusses the development of kinetic typography, wherein words are imbued with meaning beyond simply the text they are, becoming visual metaphors through the process of adopting elements which extends into the realm of more than simply just sight. Informalization is the process of expressing the idiosyncrasies of everyday human communication into language. As with any communication technology, a loss of formality in its practice is a natural development through its establishment as a normal medium in the expression of language. In a similar vein, emotivization describes the subjective quality that is inherent to the practice of writing.

Throughout the class, we have discussed how we may effectively communicate to an audience through the use of various visual elements. Kinetic typography is one of these elements which becomes significant in its metaphoric capability which allows it to challenge the boundaries of written text through the elements of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization.

I found the most interesting aspect of the paper to be the discussion of how the development of kinetic typography software within a blackbox is somehow antithetical to its aims as it strictly codifies the practice of kinetic typography to adhere with the intentions of software developers. However, kinetic design may be harnessed if we were provided with tools that have greater degrees of freedom in how text is designed and moved. In poetry, which subverts traditional language structure for the purpose of artistic expression, kinetic design may greatly extend espressive capability of the poet through, as the paper stated, “restoring to writing the expressiveness of speech that derives from tempo, rhythm, intonation and voice quality.”

-

The Power and Influence of Kinetic Typography

In today’s discussion, I’ll be focusing on Theo Van Leeuwen and Emily Djonov’s discussion on kinetic typography. In particular, they focus on animating typography with a sense of personality, where modifications of different features could convey a “speaker’s tone of voice.” Their discussion on pictorialization, the use of simplified pictures often intermingling with letter forms, resonated with Scott McCloud’s discussion of the broader categories to which words and images combine in comics. For example, the presence of emoticons can often serve to convey further emotion or substitute in for the emotion left out in text. Leeuwen and Djonov’s discussion on informalization also reminded me of the Spiekermann reading focused on looking at type. Both authors empathize how typography has a certain personality, that of which can be modulated through changing different features (ie. Font width, length, style, etc.) The concept of emotivization dovetails well with our discussion on Neil Cohn’s work “The Semantics of Chicago Union Tribune Advertising,” where emotion can serve as a powerful tool to capture either the reader or the designer creating a media. Dynamicization focuses on the fact that whatever “static must become dynamic,” which relates to our Dondis’ readings of how visual elements can contribute to a sense of “movement” which is more often implied than actually expressed. A grammar kinetic design focuses on describing kinetic typography as a “language with a lexicon and a grammar.” As such, being cognizant of the state of a process can be instrumental in crafting animated movements in typography. For example, a powerful example of an effective movie title sequence can be seen in the Marvel franchises’ introductory. In particular, it leverages both a familiar theme song as well as scenes from past MCU movies to convey a dynamic sense of movement and upbeat feel for the audience. The transition from the silhouetted movie-frames to gun metal font is also an effective use of kinetic typography.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SkMUjilx_M

-

Kinetic Typography

Van Leeuwen and Djonov, in their essay, pursue a historicized sense of kinetic typography and its technicalities in how kinetic typography achieves its effects. Their opening description of kinetic typography is almost synesthetic, with an impressionistic sense of verbal tone conveyed by, for instance, color contrast. However, they very explicitly pin down shortly afterward that they had had a similar theory about smell and impressionistic, individualistic experience—only to realize that smell was in fact a structured “language” that was refined the organized by experts into units of organized meaning. The part of the essay I found especially impactful was the discussion of technical guidance and limitations as being in the hands of software developers. This analysis felt borderline Latourian—ie, users are trained into behavior by technology. (I also found it a little funny that in talking about technicalities and constraints, the journal editors couldn’t decide if they believed in the Oxford comma or not.) The boundaries of such an artform of kinetic typography coincide with technical boundaries, in a way that calligraphy never would (outside of obeying traditional forms). But those boundaries also help to define the evolving set of meanings that can be transmitted and understood through experimentation and repetition.

-

Kinetic Typography - Jumana

The author argues that the main innovation drivers to introduce kinetic typography are the concepts of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization. These concepts relate to other ideas we have explored through the multisensory experiences to provide meaning. Specifically, what we have discussed in our comic readings and typeface design—writing boom in comics, instead of drawing an explosion. The writing becomes the picture, embodied with the scene’s dynamics, emotions, information, and context. In this case, as the author puts it for informationalizaton, “make the text rather than the speaker say it!”

The author explains that language has resources for expressing accurate or inaccurate statements. The same is for pictures, they show a representation of real things that look unreal, and the opposite is true. The grammar of kinetic design might open up new venues for creativity. We can see and read the meaning of things through language. We rely on the grammar of things connected together into meaningful wholes. Images are like grammar. They can construct, persuade and send messages. In a related article by the same author, he claims that the grammar of visual design is no longer inverted by artists but by software designers. He explains by giving an example of Computer-generated images representing what their creation has made available. So any kind of new imagery is dependent on that.

The split in the text represents the split in the personality of the character.

The split in the text represents the split in the personality of the character. -

Different elements of Kinetic Typography

During this week’s reading kinetic typography was defined through the concepts of pictorialization, informalization, emotivization, and dynamicization. All of these concepts relate to previous readings we have discussed on the techniques and strategies that transform typefaces to have a deeper meaning and sense of completion.

To dive in more specifically, pictorialization reminded me of picture and text combinations on “Understanding Comics”, since in kinetic typography, the typefaces take the role of both the picture and the text and “express meaning both lexically and kinetically”.

Informalization and Emotivization reminded me of the Spiekermann reading on typefaces, where it discussed how a specific tone or emotion is evoked through details in the letters, by changing width, font, size, and other subtle or evident characteristics. Emotivization aims to have the typography become something that is “believed and felt, not just understood”. So for example, for a round soft font to be collectively portrayed as welcoming, soft, safe. Informalization is used as a “technology to enhance text with speech-like expressiveness” which is really getting at reclaiming the non-verbal and informal cues that are inherent to speech but not necessarily present in text to aid in the essence of the message behind the typography.

Finally, Dynamicization, adds a sense of movement, liveliness and just overall character to typography that can mimic our own human emotional responses. Like for example, the case when the word fear is animated to shake to emulate our shaking when scared.

All of these different elements contribute to creating a new language with its own grammar that can be universally understood and applied to tell stories.

-

Comments on Semiotics of Kinetic Typography

I appreciated this reading because I had never considered kinetic typography as its own medium, but it’s clear from this reading that it has its own ways of communicating meaning that are worth analyzing. Pictorialization as discussed in this reading relates strongly to McCloud’s idea of the Big Triangle, specifically the axis between reality and pure meaning. By mixing pictures with letter forms and making the text move in ways similar to things we can recognize in the real word, we are shifting text left on the triangle. This opens up a whole world of possibilities, as once text is free to move around the triangle it can also be moved upwards to be closer to the picture plane and be more abstracted for its own sake. The simple act of pictorialization allows artists to flood in and explore the opportunities inherent in kinetic typography. Informalization can be connected to the reading we did on morphic semiotics, as all text inherently engages with the viewer in a certain context. Through informalization, we can change the way the reader interacts with the text and their mental representation of it, opening the doors to brand new ways of thinking. Emotivization can be connected back to the section of the McCloud reading on synaesthetics, representing the other senses through image. Through emotivization, kinetic typography can invoke an array of meanings far beyond what text can do alone. Dynamicization is also the most similar to McCloud’s idea of completion, but while comics can invoke movement between frames, kinetic typography actually can move, allowing it to communicate more through its motion. A grammar of kinetic design can allow new venues for creativity as it allows for the construction of additional meaning by combining different elements, as opposed to the current lexese where the items can only represent meaning individually.

-

Barthes and Sontag - response

I was focused in my reading in the underpinnings in both Sontag and Barthes’ writing about photography’s relationship with reality—or at least, our perception or experience of reality. Barthes speaks from a corner drenched in phenomenology, where Sontag is far more formal and technical as a critic. However, both dig at the underlying sense that the photo retains a greater claim on the subject’s being than the subject itself, in varying senses.

One subject that Sontag discusses is experience—say, a tourist on vacation. The report of the image makes the experience of the trip real—preserves and reifies it, and, as Sontag observes/warns, supplants the actual doing of the trip by simple virtue of outlasting it, but being more permanent and more easily referenced than memory itself. She opens her argument with the example of Plato’s cave: a realm where images were understood to be reality. In her conception, “images that have virtually unlimited authority in a modern society are mainly photographic images, and the scope of that authority stems from the properties peculiar to images taken by cameras” (153).

Barthes approaches the same point with his more mystical and self-centered philosophy: his experience of being photographed becomes his baseline for the philosophical argument he makes that the Photograph is a spectral borderland that could easily embody Death, but also that it ferments a sense of adventure (which would be an argument familiar to film critics of early documentaries in which a sense of being there was so central to the experience of the film). Barthes writes, The Photograph (the one I intend) represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object…I am truly become a specter” (14). In Barthes’ estimation, the Photograph’s claim on reality is intertwined with his ideas of his own consciousness: “I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image. The transformation is an active one: I feel that the Photograph creates my body or mortifies it, according to its caprice” (10-11). Sontag states far more plainly: “photography’s progress has made ever more literal the senses in which a photograph gives control over the thing photographed” (157). Again, the thing photographed could well be an experience, reified to an image.

Barthes and Sontag both work with the slippery moment of thingness involved in photography: the instant of preservation and representation that has such an authoritative hold on reality for the viewer. Sontag has a number of beautiful extrapolations on this theme, including a favorite of mine where she draws on Balzac’s “ghostly” theory (that would get along very well with Barthes’ “spectral” one) to describe any person as an “aggregate of appearances” (159). But most explicitly, she drives home this reality-image relationship with a technical-level statement: “The mechanical genesis of these images, and the literalness of the powers they confer, amounts to a new relationship between image and reality” (158). This is, in effect, the image-world of the chapter’s title: the supplanting of an image’s authority over experience, the image’s ability to lay greater claim to reality than experienced “reality” itself.

Neither Sontag or Barthes are being necessarily alarmist; both seem fascinated by the authority and power of an image, even eager to perceive the range of photography’s power. Barthes’ mention of feeling inauthentic in photographs of himself, though, is telling. What is in the photograph, after all? It isn’t Barthes, but it is the only way a reader like me will ever physically encounter him. In all effect, the image of the man has become the reality.

In terms of title sequences, I am a huge fan of how the title cards for The Green Knight (2021) create a sense of space and of transformation from instant to instant. Unfortunately, they are also unique in that they are scattered throughout the film, and I could only find a brief moment of them in this clip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hF3c0rIJujA&t=10s

You can get a sense of their stylization via the onscreen text in this video however:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI189R6JyYI

-

photographs

In the passage, Barthes discusses the philisophical underpinnings of photography as having deeper roots than that of simply capturing a moment in time, the act of capturing a photograph having significant influence over the consciousness of the “spectator” distinct from the photo’s subject and photographer. Barthes terms two core elements of photography: studium, the relationship between the photograph and the context in which it was captured and puntum, the personal relationship with the prospective observer. The discussion in these last chapters reminded me of Andy Warhol’s work in reprinting photographs. I had always thought these pieces of work to be quite unrefined and meaningless. What is there to be gained from a series of soup cans? However, throughout this reading, I thought about how these photographs were so impactful due to how distinctly present studium and punctum were. Studium in highlighting such an iconic commodity as the Campbell’s soup can and cementing it in a point in time and punctum in how these commodities are so pervasive in our personal lives that they inadvertently become a part of our individual consciousness.

The series of photos evoked almost a sense of otherworldliness in immersing the spectator immediately in a narrative Gerz crafted related to the photo. However, the associated texts did not simply describe the photo, but positioned it as a snapshot in time of a broader story occuring in the background. Some of the works of the French wall I found to be a bit confounding, especially the first couple of ones, which were more abstrac. However, I found the last couple to be similarly intriguing as the text spun a story with no premise as if capturing a narrative in a moment in time, similar to the function of photographs.

-

words and pictures

I had not thought about how both art and writing, two practices with fundamentally same aims were so separated in both practices today. We take it as a given that writers and artists are different. Although both dedicated to the pursuit of communication and tapping into our shared human experience, these disciplines are often viewed isolated pursuits rather than ones that are intertwined. For the concrete poetry design project, this reading has lead me to think more deeply about how to develop a dialectical relationship between the words of the poem and the fonts and design that I choose. Rather than simply choosing design elements which relate to the poem, I will consider how these design elements can have meaning in their own right equal in significance with the words of the poem.

-

McCloud Chapter 6