Commentary

-

Week 11 Commentary - Meenu Singh

Tufte, Chapter 6: Narratives of Space and Time

I thought this chapter of Tufte was very interesting, especially because many of the examples felt like they tied back to some of the prior chapters. One section that interested me was the part about timetable and schedule design. Tufte writes that “Schedules are among the most widely used information displays” and says that there have been efforts to organize schedule information for 150 years. This stuck out because the widespread nature of schedules/timetables made me take for granted the design choices that go into making them. I also feel like there is a new wave of trying to redesgn/display schedule information because of the shift towards digitizing schedules and displaying them effectively in the mobile/web space.

This chapter also made me realize how challenging of a task it is to represent spatial and temporal information on a flat plane. With technology we are able to filter out information and move between different representations at the click of the button. However, on paper there are several limitations in terms of dimensions that can be represented before the information becomes too dense and cluttered for paper. One effective example I found was the Czechoslovakia air transport map. The balance between space and time information really felt effective and overall the map felt really clean (not too information dense + there was plenty of white space). On the contrary side, I was quite confused by the serpentined data representations like the Tokyo water supply bar chart. As much as I tried to look at the charts, I genuinely could not understand why someone would ever choose this representation because it felt both confusing in terms of conveying information as in addition to being aesthetically displeasing.

The bus schedule as an example of a graphical schedule was another point of interest for me. Initially I thought the jumbled lines during peak rush hours were a point of design failure, but after reading the description I realized that the relevant information is simply being conveyed through a different property of the schedule: its line density, as opposed to the familiar numerical representation that may be used for the rest of the times. I feel like this really shows how one can play with information representation in unique ways without compromising its functionality.

-

week 13-1 commentary - meenu singh

Chapter 4: Small Multiples

I thought this chapter on small multiples reinforced how powerful it is to be able to present information within the “eyespan”. The juxtaposition of those images allows us to draw comparisons and single out key differences at a glance. I really liked the train example and how Tufte described it as “a scope of alternatives” or “a range of options”. The example kind of reminded me of shopping catalogs or online stores where the products are placed next to each other so that you can decide on a design quickly.

I was expecting very data driven examples in this section (like the smog/air polution chart we had previously seen in chapter 1) so I was surprised by the example of Mural with a Blue Brushstroke which displayed the different inspiration images to parts of main painting. It feels different than the other examples of small multiples that are placed together to draw out comparisons between each other. In this example, it felt like the inspiration images were being connected only really to the main image which I thought was interesting.

-

Week 12.2 Commentary (Isabel Báez)

Tufte highlights the relevance of how multiple small designs lead to comparisons that enrich the data being presented. By drafting out multiple, sequential details, the audience is giving context in the form of change.

His train example, which accentuate’s the meaning behind different light signals for railroad employees I found personally very effective. The thin lines of the train, in contrasts with the dots of color created a clear image. It also made the differences between frames clear. However, there were some different elements (white lights in the middle) that also showcased examples between frames and were not very clear at all. Their lack of color make them get lost within the complex shape of the train. Adding color to these or more accentuation would’ve grouped them with the other differences and made them more evident. Although I do like the train’s detail, another alternative would be to simplify it as well.

I liked his example of Linchestein’s New York mural painting. Antupit disects Linchestein’s work and showcases the contrast between the inspirations behind the work and the actual mural. I would’ve enjoyed to see a little more marked connection between both components. The dotted lines they use to trace the inspirations to the mural are not very noticeable and sometimes get lost. I would’ve liked to be very clear on what part of the mural the inspiration was referring to, so I would’ve liked closer tracing.

-

[chxchen] Commentary 19

Tufte starts this chapter with a quote I really like: “Confusion and clutter are failures of design, not attributes of information.” I really like this quote because of the ownership and responsibility it gives the designer to decode data into visualizations. Layering and separation help segment aspects of data. It’s tricky because various elements will always interact just because they are present in the same space, regardless of if the designer intends for these elements to be perceived together — a concept known as “1+1=3”, because the combined information becomes something else.

The first example with the parts manual was quite simple and easily understandable. I think a more complex example would’ve actually been more beneficial, especially with more layering, maybe for different parts of the item. However, it was a very good example of colors helping differentiate using annotation. In contrast, I disliked the later city map where it was honestly a lot more difficult to differentiate between the color differences the author was talking about.

The concept of “data imprisonment” is very interesting to me because the common perception of data is usually using tables with a grid system. However, I definitely see Tufte’s point — I really like spreadsheets where different cells are merged and add more dimension and understanding to the data given, for example. I think looser divisions are also more aesthetically pleasing to me — for example, not just heavy border lines for each cell, and use of color blocks to separate. I really like the example with the music staff because I’ve noticed this particularly with handwriting in music staff books that more bolded staffs make it more difficult to write things down and everything looks less cohesive even if it’s played the same, and I also really like the concept of layering using negative space.

-

Week 13.1 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

One thing that stood out to me was Tufte’s dislike of strong grid systems. For instance, he demonstrates through the New Jersey Transit timetable redesign that removing harsh lines with subtle shading can help calm the display and remove visual barricades. He even goes as far as to state that grids “should be used only when they are absolutely necessary.” However, I’m not sure if I agree with his statement. Most figures and tables in research papers still use defined grid systems even though they are visually less appealing because they clearly define rows/columns and minimize mistakes when reading the table. It made me wonder how designers should balance visual appeal and practicality.

I also found the use of color to create a separate layer interesting. I liked how Tufte brought back principles from earlier chapters, especially when discussing the Berlin map and the way they used strong colors sparingly to create an effective display. I particularly enjoyed the Rome river map example, where a very subtle change in hue of the river was still able to reduce the feeling of clutter in the map.

-

Tufte Chapter 3 Response - Mikel

Most of all I think this chapter helped me think about the ways that the organization of data can sometimes make it harder to navigate. Especially with gridlines that are meant to delineate different categories, I see how only implying them or being very subtle with them is effective if using the ways humans naturally group things together.

The only time it didn’t feel as impactful was with the marshaling signals example. I agree the bottom one looks better, but I really don’t think the first design had any hindrances to understanding it. I think the bottom design did make it more visually attractive, but didn’t make any of the information any more clear. In comparison I think the statistical graph example right after is a good example of this consideration because there actually needs to be comparison between the data boxes. You wouldn’t need to compare between different signals, so I think the thick lines are unnecessary but also not harmful in the orignal.

-

Ch 4 Small Multiples - Trudy Painter

I really liked this chapter. It reminded me rich prospect browsing interfaces, those that “combine a meaningful representation of every item in a collection with a number of emergent tools for manipulating the display.” By using small multiples, I feel the scale of a collection of information. And each of the multiples provides context for the slight variation (ie the train light signals).

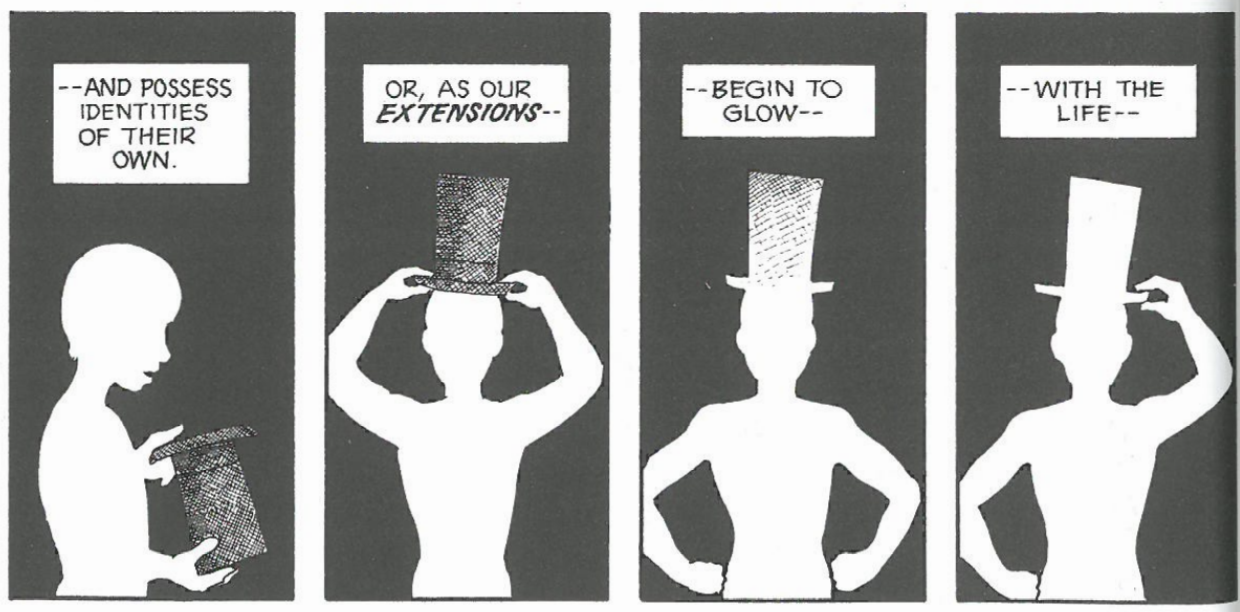

Many of the diagrams feel imaginative. Like exercises in world building (the different bugs and pictograph characters). I thought this chapter had the most personality of the readings.

-

Week 13.1 Commentary - Audrey Gatta

Envisioning Information, Chapter 3 - Edward Tufte

In the chapter, Layering and Separation, I found that the most effective methods of identifying interacting information was the use of color as well as the use of negative space. The example of the IBM Series III Adjustment Parts Manual demonstrated how the use of color creates a differentiation between the parts themselves and the annotations — even though there is so much information on the manual, it is still possible to find which part corresponds to each number. Paul Klee’s sketch had a lot of parallels with the manual, because there is a clear separation between the black line and the red commentary (he also played around with thickness too). The Tokyo map shows different elements in different colors on a more muted background, with only a few colors being brighter (red and yellow), which connects back to the “first rule of color composition”. The other aspect I found interesting and effective was the use of negative space. In the same example of the Tokyo map, the white lines, or negative space, between the buildings highlight the roads and paths themselves. Also, in Gaetano Kanizsa’s drawings, the intentional spaces create the appearance of shares in the negative space.

-

Week 13.1 Commentary - KCG

I found the maps of the birthplace of Chinese poets to be very interesting, and immediately it made me think about maybe the places of the highest concentration were linked to the most populous, the most educated, and the most powerful areas of China during the corresponding time periods. Of course, this connection between the birthplace of famous poets and where power in China was located at the time is not explicitly explained by Tufte, I just assumed this, but then later in the reading when he mentions making comparisons among geographic distributions of sea-goddess temples and birthplaces of Tang, Sung, Ming, and China poets” I immediately took notice and thought that any connections would be a correlation, not causation. Generally, I’m confused why he is trying to compare the two, but I see his point on how because that map was on a separate page, you cannot easily compare the map with the other four (which would be on the same two pages, even though in digital format, we cannot discern this difference). This discrepancy between comparing in a digital vs a physical format is interesting to me because, in the digital world, it is much easier to compare things if you want (assuming the format of what you are comparing is the same) since you can more easily manipulate the data visualizations by shrinking them so they fit on the same screen, by duplicating the book and then flipping each copy to different pages, etc. If this were a physical copy of the book, I couldn’t easily do the same thing - I would have to purchase or procure another physical copy of the book to compare, or I could rip out the pages (but even then, the maps would be on the same sheet, so I couldn’t view them at the same time).

I found the river and mountain comparison chart to be interesting, too. Like Tufte said, the lakes add a depth of meaning to the river chart. I’d also argue that it seems like there is more meaning in terms of knowing where the rivers start and end (what direction the river flows) as well as how wide the rivers are relatively, even if not to scale. The mountain comparisons are less successful to me, too because they are spaced too closely together, and it is difficult to read the corresponding labels. The mountains are also drawn the same way, even though in reality I know these mountains have unique shapes. This is truly an instance of an embellished bar graph - one that is difficult to read, too.

-

Week 12.1 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

I thought Tufte’s philosophy of clarifying with the addition of detail as opposed to simplifying graphs was really interesting. I think the different types of information that can be conveyed at the Macro/Micro level was best examplified through the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. While zooming into each names in the memorial give insight into individual stories of the veterans, looking at the memorial from further away conveys the magnitude of the loss. I also thought it was interesting that they decided to arrange the names by chronological order as opposed to alphabetical order.

One example I didn’t understand was the graph displaying temperature and conductivity of different elements. Tufte seemed to find the display very effective–“Note how easily these displays organize the material, recording observations from several hundred studies and also enforcing comparisons among quite divergent results …”. However, I personally found the individual plots way to cluttered and distracting from the overall trend. It made me wonder where is the line between informative/excessive and what is the “ideal” level of detail that designers should strive to achieve.

-

week 12-1 commentary - meenu singh

Tufte: Chapter 2

This chapter on micro/macro readings was very interesting because it connected informational design/map making to design principles we have seen in earlier reading where we learned about the importance of juxtaposition and contrast that arises from a wholistic view of information. I really liked the example of the conductivity/temperature curve because I find that it is effective at providing a lot of dense information within a small area. At first I didn’t understand what the point of graph was, but after reading the description I think it provides an overaching look at the same experiment conducted over time. I also liked the improvement described about numbering the curves chronologically as opposed to alphabetically because it adds another dimension and creates a story for the graph. think the stem and leaf plot examples are also very interesting because I would have never thought to use them for the purpose of train schedules. However, they were able to effectively use it as a way of preserving characters, improving readability, and saving space. Aestheticaly, I didn’t really like the back to back stem and leaf plot as much.

The chapter overall reinforces the idea that “To clarify, add detail”. The author seems to have a fairly extreme take on this, because they state that simplicity is an aesthetic choice not an information design on. I’m not sure I agree with their statement that “clutter and confusion are failures of design, not attributes of information” because I feel like there are places where the purpose is to convey information quickly. In places where speed of processing information is crucial, having a detailed wholistic view is anineffective information design choice, not just one of aesthetics.

-

Week 12.1 Commentary - Isabel Báez

In his second chapter, Edward Tufte dives into the combination of micro and macro readings in visual design and physical structures.

He speaks of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., and explains the complexities behind the contrast of the actual structure’s macro design, and the micro readings of each soldier’s names. Similar to Tufte, I agree that stemming away from an alphabetical, telephone book asjacent micro design was the right decision. Grouping fallen soldiers by name strips them away of some sort of individuality, as each individual name gets lost in a see of similar one. Moreover, the value in the chronological ordering is much more significant in the context of a war.

The aspect of the Manhattan Midtown diagram was less comprehensible to me in the context of the macro/micro design. Tufte mentions that the details supplements the drawing of routes accross different shops, specific locations, etc. However, I think more detail is needed (such as perhaps adding inviduals performing daily activities) to give this additional dimension to the diagram.

-

[chxchen] Commentary 18

Tufte discusses the concept of micro / marco in this chapter: building something large using small units.

Some of Tufte’s examples really resonated with me, but others didn’t make a lot of sense. For example, the poster with the hand composed of smaller hands did not seem like an effective example in my opinion. The poster seemed very different from the other uses Tufte talked about, which dealt with more data visualization and practical uses of micro / macro.

Others of Tufte’s examples felt a little like they were trying too hard, such as the graph on electrical resistivity. The graph was still quite cluttered, and Tufte’s praises would apply to any graph – all graphs are made of smaller data points. I think it made more sense when he talked about this in application to a larger map, because the smaller data points are different from just shading in areas of the map. The idea of stem and leaf plots as effective use of micro / macro was also very convincing to me.

I like this line towards the end of the reading: Clutter and confusion are failures of design, not attributes of information. I think it really encapsulates the usage of micro / macro as a skill in design – effectively making lots of information fit concisely.

-

Week 12.1 Commentary - KCG

For certain data, detail and the whole set are both equally as important (either within the same context or for differing but both relevant contexts) and in those cases, data visualization and presentation should include details and the whole picture; by the whole picture, I mean a way in which the viewer can get an understanding of the data (in number sets, this can be the number of data points, the average, the median, the range, etc) without getting bogged down by the details. An example of this that Tufte examines is the design of Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC. As the viewer, you can access the “details” (the individual names of American casualties of the war, the chronological order in which they died) as well as the “greater picture” of the relative amount of casualties of the war during its span. However, I would argue that the memorial still does not do that great of a job of conveying detail - if you were to want to find a specific name engraved within the granite, you must use a separate index entity in order to find the name.

A more effective design is the stem and leaf plot, especially the one of the 218 volcanoes, since you can see the individual volcano heights, and you can also see the distribution of the heights. However, in terms of a data usage perspective, the plot is more difficult to deal with than a list of the data points arranged from low to high or vice versa. However, this might be just because the former is the form in which we are most used to receiving data in.

-

Tufte Chapter 2 - Mikel

Overall I think I best understood the motivating principle behind “to clarify, add detail.” I related it to the idea of “trusting the reader,” especially with Tufte’s paragraph at the end of the section detailing all the ways people parse out an informationally dense image. Sometimes in writing people want to clarify by being super overt, but that shows a lack of faith in the reader. Instead, efficient but subtle methods should be taken to relay information using the known ways that people tend to extract information from a busy scene.

Two examples that I found confusing were the graph about copper conductivity, and the Tokyo population maps. I thought the labeling on the copper graph cluttered the information too much, it was an important part of the graph of course but the lines for the actual graph and the lines to label those made it very hard to follow. I liked the Tokyo population maps, but Tufte said residents are still able to pick out their own square. I don’t see how someone could do this without more information on the map helping them pick out where they live. I still think it’s a good map, but for an individual I don’t think this is the best example of micro/macro design.

While I was glad to have some takeaways from this chapter, I think I struggle with Tufte readings because of his insistence on only using existing examples. I would have liked to see something from the ground up: with a given data set/audience/goal how he would use the tools of the chapter to create a display. I think there are so many intricacies to the examples he puts forth, that he doesn’t really talk about, that make them not feel like a great way for me to learn.

-

Tufte Chapter 2 Commentary - Trudy Painter

I thought this chapter was too general. It could have benefited from dividing up the types of information you are displaying.

For example, Tufte starts out by claiming, “to clarify add detail.” He is referencing Constantine Anderson’s map of NYC. This map builds upon an existing, clean grid system. Anderson is able to add detail to the portrayal of buildings, which have already been neatly compartmentalized to their geographic constraints.

Then Tufte shows examples of more organic, unorganized data (the temperature/conductivity graphs and Tokyo population density). Of course theses are harder graphs to read. The data is less regular, and its harder to fit a consistent grid system approach to them.

If I were Tufte, I would have adjusted the final statement to switch simpleness for regularity → “the regularity of data and design equals clarity.” This is less of a contradiction as you could add detail in a regular grid system to clarify instead of clutter.

Also as an aside, the Tokyo train schedule system reminds me of Maison Margiela’s garment tag system.

)

)

-

[chxchen] Commentary 17

This was an interesting read that I felt had very strong ties to our previous Tufte reading on escaping the flatland. For example, the section on schedules tied back very well to the train/rail schedules we discussed in the previous reading. Tufte makes a great point about how schedules are designed for the needs of a variety of audiences and are very rarely multipurposeful – this was something that I definitely thought about in the last reading regarding the complex railway map that would’ve been useful for an operator but less so for a passenger. I liked that Tufte dove deeper into a criticism of the original New England train table, and I agree with his criticisms. The variety of ways to arrange train schedules is really interesting – I didn’t like the ones with the diagonal lines because it ended up being too cluttered and not exact enough for me to read, but I think the idea is very solid and depending on the complexities it could look really good.

I thought the astrological mapping was an interesting case study, particularly looking at the development from a day-to-day mapping of Jupiter and its satellites to the continuous motion of its waves. From an educational standpoint, we can also see that mapping occurrences in different ways can change a lot about how they are perceived.

-

Week 11.1 Commentary (Isabel Báez)

For me, the first graphical visualizations depicted by Tufte were a little hard to follow. The overlaid map of the New York bus system was unclear. The aerial view was very dark, and made the routes hard to follow. Morever, it was complicated to draw the connection to the graphical representatiom. I do, however, find value in the density created by closer lines for buses that were scheduled close to each other. This charged component is easily connected with the idea of “being busy”, which makes sense for a busy schedule of buses.

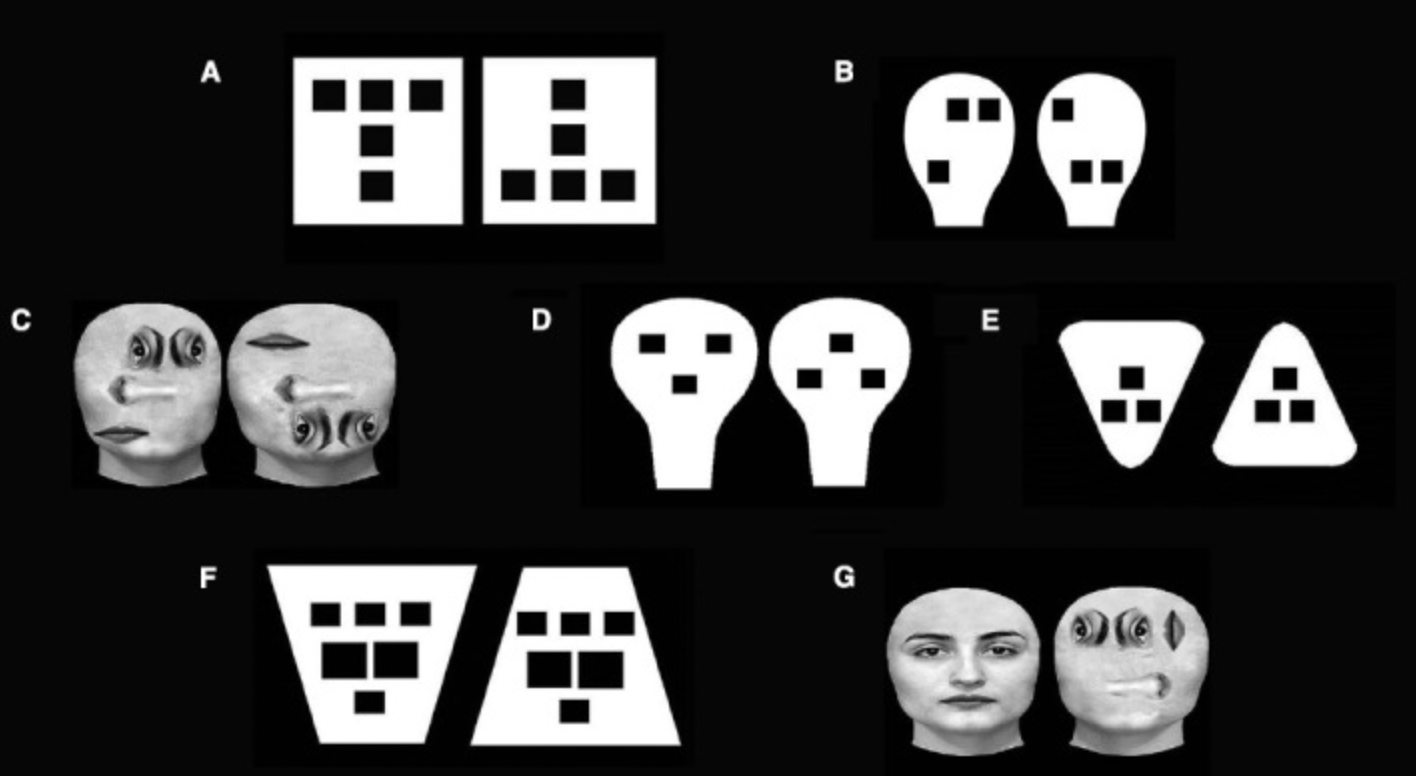

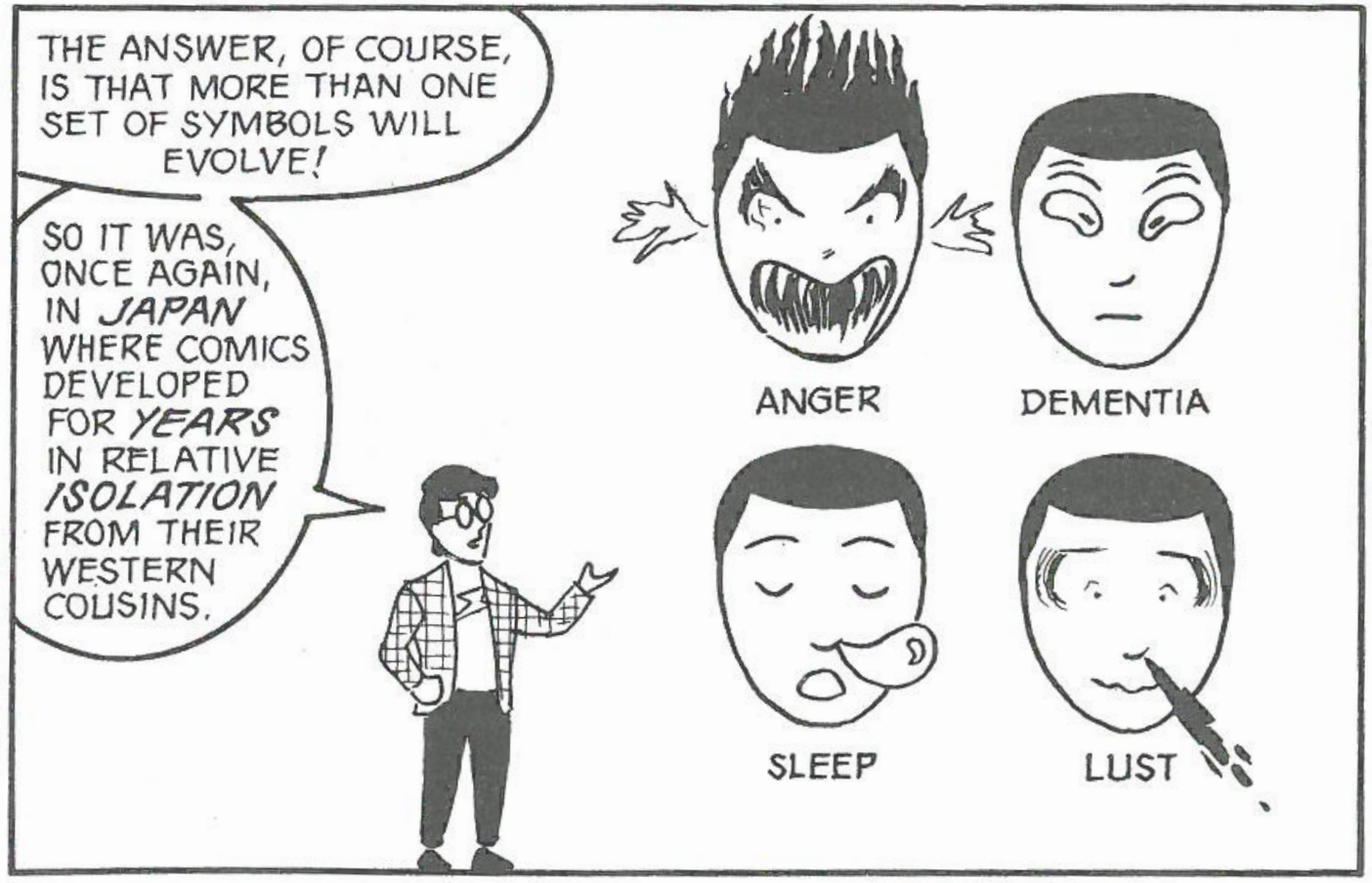

I did enjoy the representations of dance. The first, very symbolic ones, were hard to follow, and made me question their universaility. I wondered if the symbols used were something familiar to proffessional dancers, or just a design choice at their moment of creating. The more figurative representations were easier to follow and more comprehensible. This reminded me of the McCloud reading, in which he states that humans map their face, or in this case body, everywhere. Perhaps that is why I perceived these diagrams to be more understandable. Moreover, the last diagram with the adorned text reminded me of a static version of dynamic text, as the movement of the text makes reference to the flow of the dance being represented.

-

Week 11.1 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

I found the serpentined data representations interesting. For both the river comparison chart and tokyo’s water supply chart, the data curves and bends around to work with the graph’s grid. While I found both examples really visually interesting, it made me wonder why the designers chose a sepentined data representation as opposed to just rescaling the graph. The serpentined graphs made it harder to visualize the differences between different rivers/water supplies, and since the designers can choose any scale, I was puzzled as to why they would chose to work around the space limitations this way.

The most difficult-to-understand graphs in the reading for me were the dance notations. While I really liked all the “art of dancing” diagrams and the way they played with perspective to give information about different dance steps, the way that music notes were marked made it difficult to follow. The birds-eye view where they abstracted different steps into symbols were also very confusing to me without a clear key to reference.

-

Week 11.1 commentary - KCG

I found the train time table example to be interesting because in my own experience, I sometimes get confused by how to navigate them - like when looking at the commuter rail schedule, or when I’m at the train station, and trying to figure out which direction is a train is going with high stakes, since they often are going in opposite directions. The redesigned example, even though in my opinion, is no more aesthetically pleasing than the “bad” example, at the very least does a better job of differentiating if the train is going to New York or New Haven by having it in two different places (as a title, and then as a column header), and the arrow between the two locations is a nice visual, non-verbal indicator of directionality, too.

I found it interesting that Tufte brought up another dance visualization as an example. I don’t personally dance but I have a lot of friends who dance, and also have family friends who are professional dancers and they do not use any dance notation (dance notation is primarily just for documentation) and still rely on learning and teaching dance from live choreo and doing by example. This brings up the question, what are the limits of the use of visual documentation?

-

Week 11.1 Commentary - Audrey Gatta

Envisioning Information, Chapter 6 - Edward Tufte

Tufte really highlighted the omnipresence of the dimension of time within information design through the many examples of timetable designs that he provided. I was especially interested in the New York to New Haven train timetable example: immediately when I saw it, I thought about how it could be redesigned into two columns for weekdays and weekends/holidays, so that the times within one day could all be aligned and the viewer’s eye would not have to awkwardly transition from one column to the next to find the right time. It was cool to see this idea within the redesign on the next page. (I also appreciated his comment that the biggest issue is that the duration of this train journey is still the same as it was 70 years ago.)

It was really cool to see the examples side by side of the collegiate rowing contests “bump charts” and of the timetable of Wagner’s operas from writing of text and music to first performance — the visual similarity was striking, despite being timetables with completely different contents.

-

Week 11 - ChartJunk, Hanu Park

Tufte:

I agreed with most of his design points for maps, although I did face points of confusion. Particularly, in his points with computer windows, he described yellow as the only suitable color. However, computers today have no border color, and in the past I believe Windows systems used blue (?). I wonder what influenced companies to reduce color from their UI, and if that trend will continue.

Second, I had a bit of confusion with his fourth design point. I did not understand what he meant, and the examples he chose did not display the point completely, in my opinion. To get this idea better, I wish I saw an example of non-intertwined maps.

Other than that, his points made sense to me and pointed out aspects of good maps that I had not formalized beforehand.

ChartJunk:

This study condensed into words my sentiments from the previous class. The author had a moderate viewpoint and objectively weighed the pros and cons of graphics in data representation. I agree with his three points about the merits of graphics, but also with his definition of chartjunk. He doesn’t define in strict terms what constitutes as chartjunk, but describes a general characteristic, where readers can define their own thresholds for what constitutes as unacceptable.

-

week 10-1 commentary - meenu singh

Tufte - Chapter 5:

I really enjoyed the continution of Tufte’s writing and focus on usage of color in information design. Tufte outlines four categories of functions of color: to label, measure, represent or imitate reality, and to enliven or decorate. I found the distinction between the different uses of color is a little vague. The categories themselves make sense to me, but in the example case given of the Swiss mountain map, the colors distinguishing water from stone was considered an example of labeling, but I feel like it is also an imitation/representation of reality because the colors used correspond to the color of the natural elements.

The rules provided on how to effectively use color reinforced a lot of intuitive understandings that I had, such as not using too many bright colors, or the increase in effectiveness when contrasting bright focal points with dull backgrounds. However, one example of the color usage stuck out to me because I didn’t find it very effective. I can’t tell if I’m used to standard mathematical notation but I honestly found the colorful proof of euclidean geometry to be difficult to parse. However, this made me wonder if my understanding of the more complicated proof is a function of me not knowing the language of the symbols yet.

Few - Chartjunk Debate

I think this paper points out a lot of important flaws in the study described in the paper. Designing an experiment that has controlled assumptions is vital to producing results that can be reproduced and also more widely accepted. Even before reading this paper, I had reached the conlcusion that Tufte has a little too much faith in the power of data. Not all data is processable in its simplest form and requires the use of embellishments to make points. I appreciate Few’s acknowledgement that “no one graph can display the full story that lives in a set of data”. However, I didn’t quite understand the jump to the characteristics Few describes must be in graphs in the typical manner and wanted to know more about the evidence for these characteristics/how they reached this conclusion. It felt like the paper dispelled the credibility of the study effectively, but didn’t provide reasoning for the conclusions suddenly presented at the end.

-

Week 10.1 Commentary (Isabel Báez)

Edward Tufte

Tufte discusses the way that color used to display data, along with its benefits and shortcomings. Digitally, color can provide significant advantages: it reduces video glare and, moreover, its edge definition strives away from grid-like representations. Sticking to nature-based color is also better on the eye, as they are more familiar and prevent the garnishing that stronger, non-significant colors would bring.

Tufte evaluates the differences between differentiating scales by values versus by hue. Although recognize the faults in the ocean mapping example he presents, where similar values may be hard to tell apart, I do think its benefits overpass those of the rainbow alternative. The ability to relate the blue to the ocean, and the darker values to more depth, is much more valuable. As Tufte mentions, rainbow colors have no meaning towards the mapping, would be harsh to the eye, and would need some kind of legend to give them meaning.

Steven Few

The findings of Few’s study, comparing information digestion from embelished versus plain graphs surprised me. I hypothesized that overtly embelished graphs would distract from the information displayed, in contrast to their plain counterparts. However, Few expresses that participants were able to recall the information of embelished graphs much better. I suppose his justification makes sense: when information is accompanied and supported by multiple visual elements, it is easier to remember. Moreover, an embelished graph with interesting elements might be more memorable overall.

Nevertheless, although I think some embelishmment is beneficial, the Holmes graphs studied by Few’s certainly over do it. The amount of detail in the graph make them very hard to understand first glance. If the amount of time that participants were allowed to study the graph was reduced, I’m sure teh results would differ. Moreover, maybe there exists some middle ground between the embelished and plain graphs presented by Few that superpass them both in initial value interpretation and in recall.

-

Week 10.2 Readings

Reading: Edward Tufte - Color and Information (Chapter 5)

I agreed with most of the points in this reading. I thought that color should be used more sparingly. I especially liked the point that viewers of a graph wont remember the order of color gradients. For example, i don’t actually remember the order of ROYGBIV as I look at color coded stock prices. These color gradients can be dangerous to use because a viewer will need to continually cross reference the color key for context.

Reading: Steven Few - The Chartjunk Debate. A Close Examination of Recent Findings

I am anti no chart junk. I know that is a mouthful. But I do not agree with Edward Tufte’s stance that charts need to be devoid of character and as minimal and stripped down as possible. Steven Few’s survey showed that embellishment is useful for a chart that can be explained in a single sentence. This feels intuitive. However, I think there will be more interactive elements to information in the future. For example, how will schoolchildren explore virtual reality information landscapes. I do not think that Tufte’s minimal landscape would be the best approach for meaningful sense making in immersive data. And I also don’t think that Few’s embellishment of simple data would help to tell meaningful stories about complex multidimensinal data. I would be interested in exploring more research on immersive information landscapes.

-

Week 10.1 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

Tufte Chapter 5

I agree with Tufte’s arguments that strong, bright colors are the most effective when used sparingly. The example of a 1970 map he showed seem to demonstrate this point, where too much bright colors resulted in a jarring effect. I particularly liked the section where he talked about color theory and how it can be used to extend the perceived visual palette of a design. When I saw the example he gave (a road map), I initially thought the darker red was a different color. However, after reading his explanation I realized it was the same red color outlined with blue. I thought it was interesting how color theory could work to create “new” colors within the limitations of print.

Few

After reading Few’s article, I still maintain my position from last week that adding embellishments to a graph can be an effective means of communicating information. For instance, the study that Few cites demonstrates that people are still able to interpret charts accurately with embellishments, and that decorations actually help with recall of this information. While some embellishments may go too far (e.g. the 2010 sales chart), I think it’s very harsh to assume that any effort to decorate graphs are unnecessary and patronizing to the viewer.

-

Tufte and Few Readings - Mikel

Tufte

I like how clearly Tufte was able to explain how color can be used effectively and how it can harm a design. I especially thought the math proof using color coding was great, because when used in combination with the alphabet-labeling notation I thought it was a greatly improved diagram over the only-color/only-letters. It reminds me of the McCloud reading for combining image with text, when both explain the same situation for clarity, and not to add meaning to each other necessarily.

I also appreciated two of Tufte’s points, that colors from nature are usefully familiar in design and that contour information can be given with thin/subtle lines, because of how they related to the Science of Art reading / Gestalt theory. Lots of the arguments in the Science of Art paper came back to our eyes perceiving certain things as pleasing because our visual processing is based on images of nature, which felt similar to Tufte’s color argument. The insistence by Tufte to only give the “presence of a line” I felt was supported by the Law of Good Continuation since people already do a lot of work to distinguish between feels by following vague contours.

Few

I didn’t really know what to pull from the Few reading. His breakdown of the study was good, but it seemed so obviously faulty that I found myself frustrated with how general the final takeaway was: to base the design on the content and audience. One of his final points, that embellishment can only enhance effectiveness as long as it doesn’t distract/misrepresent, was too general for me to agree with completely but also felt too simple as a final point that I’m not sure if I missed something.

-

[chxchen] Commentary 16

Tufte’s chapter on Color and Information was an interesting read. I liked that Tufte talked about diminishing and even negative returns when it comes to usage of color – he specified 20-30 colors, but I think it could be even less than this. Particularly in websites today, we see a range of 2-5 main colors, perhaps with varying shades that can increase the “number” of colors. I didn’t like Tufte’s example on the uses of color in information design to label, measure, represent, and decorate. Tufte seemed to just describe any scene in nature, which isn’t really information design – in his example, all the colors simply represented reality. I thought Imhof’s rules were interesting, but I didn’t agree with all of them. Rule 2 in particular I didn’t understand what Imhof defined as “light, bright colors mixed with white” – I didn’t think the example used was a good one.

I also disliked both the US map example and Burnham’s map. The US map tries to combine too many bright, bold colors, when more complementary colors or varying shades of the same color (depending on how many types are being mapped) would have been more coherent. However, I disagree that Burnham’s example is coherent just because muted colors were used with gray. The green and red definitely stand out, but do not create a pleasing effect together and are rather jarring against the background.

Steven Few’s article on the chartjunk debate was a good read and mainly focused on one study in accordance with Tufte’s definition of chartjunk. Bateman et al’s “Useful Junk?” tests the influence of chartjunk vs. minimalistic graphs on comprehension and recall. Though the study seems to demonstrate that embellished graphs are better than minimalist graphs, Few disagrees, contending with the argument that the embellished graphs were more often than not just graphics. I agree with this, but not with the examples Few goes on to use. I particularly didn’t like his example of an embellished graph – it definitely used a lot of features inappropriately, and while I would describe the graph as chartjunk, I think with proper usage of the visual elements (gradients, images, etc.) it could have been a nicely embellished graph that was more interesting. I also don’t agree with the author that the minimalist graphs from the study were poorly designed. Looking at just the first example, I think the lack of color was purposeful, I don’t understand why the axes were flipped in Few’s version, and the box doesn’t harm the graph at all.

-

Week 10.1 Commentary - Audrey Gatta

Envisioning Information, Chapter 5 - Edward Tufte

I enjoyed this reading, because it provided plenty of effective and ineffective examples of the fundamental uses of color in information design: “to label (color as noun), to measure (color as quantity), to represent or imitate reality (color as representation), and to enliven or decorate (color as beauty).” This breakdown is one that I had never heard of before, but it makes a lot of sense and is quite straight forward to follow in the examples.

I liked the examples of the use color in the mathematical proofs — usually we see this represented with a lot of symbols and letters, so it can be harder to follow because you have to look a lot more closely to understand it, whereas here, you can know what piece of the diagram they are talking about with just a quick glance. It is specifically effective since the diagram just uses four colors — the primary colors and black — to represent the concept. I loved how this example was followed by the abstract pieces of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, who used very similar colors in their work, yet employing a very different fundamental use.

I agreed with Tufte claim that ROYGBIV is an ineffective scale in comparison to the clear visual sequence of tone. I think using a few colors, that have a corresponding scale of tone, is effective to create a wider range in certain cases, but a ROYGBIV scale is generally less intuitive to the viewer because each color has its own average tone, which generally does not make sense within that exact order.

Steven Few - The Chartjunk Debate

I thought the experiment that found that people recalled embellished charts better a few weeks later was interesting, but doesn’t really make the case for embellished charts, because in general people remember extremes better, whether they are good or bad. It was relevant that the readers understood the message of the embellished charts just as well as minimalist designs.

To me, the “2010 Sales” example really showed how much better minimalist chart design is compared to unnecessary chart junk — the minimalist design is far more readable and easy to comprehend. However, when the embellishments add to the meaning, then I think there is definitely a strong case for it. The next example, “Employment Costs for a Steelworker per Hour”, illustrates that clearly. The visual adds to the meaning, and the fact that the US has the highest costs is clearly emphasized. In this case, it really comes down to weather the goal is to be able to analytically compare information (such as having the lengths of the bars be to scale to visually compare one country to another), or to get a certain point across (like the fact that costs in the US are much higher).

-

Week 10.1 Commentary - KCG

I felt most of the rules were already intuitive to me. For instance, the fact that you don’t want to use too many “pure” or “strong” colors (rule), especially not wanting to put those kinds of colors together - these colors are only supposed to be used sparingly and to accentuate certain things. Tufte used the example of how in real life, extreme events are rare (such as in geography), and thus, these extreme colors should also only be used rarely, in conjunction with whatever extreme or rare events of whatever context the colors are being used in. However, I did find some issues with this reasoning, because of the definition of extreme - by the definition of extreme, it must be rare, since if there were many instances, it would not be extreme. At the same time, there shouldn’t be a parallel drawn with colors since we can actively choose color palettes whereas we cannot form mountains or crevasses as easily.

I found Tufte’s point about making color scales to be interesting. He gave the example of values to show scale, or ROYGBIV to show scale, and implied that it is more natural for humans to intuitively understand value scales compared to ROYGBIV scales, perhaps because we have to learn the order of ROYGBIV (although this order occurs in nature, such as in rainbows). I don’t think this is true in my own experience. While value scales look better in my opinion, I don’t find ROYGBIV scales more difficult to interpret - weather maps often are ROYGBIV-scale-like, and the recent COVID tracking maps from the NY Times were also not value-based.

I found Few’s article to not be that interesting. I liked how he broke down his grievances with the Batesman paper, specifically how the examples they choose he felt, were leading toward a certain result. This is something that is super important in research - how to frame your experiments to not just confirm your hypothesis or your preexisting beliefs. However, the actual conclusions - that sometimes plain charts are better than embellished charts, and vice versa is self explainatory in itself in my opinion. It really depends on the content that is to be displayed, it depends on the audience, too. Of course, if the data is simple, then an embellishment can drive home that simple point, but if the data is complicated and hard to comprehend in itself, embellishments are just noise.

-

Week 9 - Tufte Ch.1, Hanu Park

At first I had some trouble understanding the definition of “flatland”, but after reading the examples I have come to define it as the representation of ideas or data across a 2D space. I was confused because I had a hard time distinguishing between the ideas of the physical flatland, such as the screen or the paper, and the abstract values that were attached to them.

In the reading, there were several points that stood out to me. First, I agree with the idea of small multiples, which is to standardize the representation of data across multiple needed distinctions. It makes sense to keep a representation that changes specifically the points that the data calls to. One downside I do see to small multiples is the difficulty of choosing boundaries or differences that will effectively separate the sections of data into meaningful distinctions. For example, if all of the carbon emissions were vaguely similar, then all the mini graphs would look similar, and there would be less of a point to display all of the mini graphs.

Next, I will comment about tables. I agree with Tufte that tables are a standard and powerful way of communicating data. I find that they are this way because there are often times where two ideas want to be intersected, and tables do that well. However, I find that tables have a weakness when it comes to trying to display a data story with more than a few points. Yes, this could be solved with innovative headers, but at certain point the information becomes too muddled to understand.

His point at the end of the reading regarding chartjunk was interesting on many levels. I didn’t agree when he said that if your numbers are boring, then you’ve got the wrong numbers. Sometimes, numbers can be “boring” and still right. For example, I will read the weather charts even if the numbers are all in the 60’s for the next month, and those numbers are still right. I do agree that there is an established quota for conveying information professionally though, and that the concepts of striking visual design and attention-grabbing formats are not necessary and may even take away from the data.

-

Week 9.2 Commentary (Isabel Báez)

Tuffe discusses the initial movements towards three-dimensional data representation. He first references paper-model designed, which first achieved three-dimensionality, specifically in Euclid’s Elements (1570). Then, he makes references to the solar systems developed in order to demonstrate accurate planetary positioning.

An interesting example he gave were stereo illustrations, were two images were given to viewers (one for each eye), in order for them to mentally fuse them together. In accordance with Tuffe, I had trouble actually managing to merge the images in my head and create the desired three-dimensional product.

He examines Galileo’s studies of Sunspots in the 1600s. Although this process consisted of multiple studies, I fail to see its three-dimensionality. As Tuffe states, the sunspot locations were unclear to astronomers, given the lost of data of the spehre-to-circle translation. Given this, its two-dimensionality makes Galileo’s Sunspots an incomplete data representation. Nevertheless, it did achieve merits significant to its time. Previous to it, the Sun was seen as “flawless”, as, according to Aristotle, it was a “celestial being”. Galileo’s diagram disproved that.

-

Week 9.2 Commentary - Audrey Gatta

Envisioning Information, Chapter 1 - Edward Tufte

I really enjoyed this reading because to the wide variety of examples of information design, although I did find that some were far more successful than others (and Tufte didn’t really talk much about the limitations or shortcomings of some of the designs). I found some of the examples to be very confusing, such as the graphic timetable for a Java railroad line (way too much information at once), the sunspots diagram, and the Japanese travel guide (I didn’t understand the transition/connection to the right hand side). For a lot of these examples, especially the ones I found less successful, I wondered who the intended audience of the design is. For example, for the train timetable, is this for train operators who need all this information and look at this diagram all the time? Or is it for passengers, who need specific information quickly, who would be overwhelmed by such a diagram? (In this case, it served as an internal planning document for the Java Railroad, which makes a lot more sense).

Some of the examples I found more successful are the periodic table (the clear organization of elements into group, including several pieces of information on each element), the art of dancing page (combining four dimensions: the flatland of floor, coded gestures in dance notation of body motion, and time sequence), and the weather map of Japan (the symbols and drawings make this design very effective, but there is a clear limitation here in terms of dimension of the country/geography).

-

week 9-2 commentary - meenu singh

Escaping Flatland - Tufte

I really enjoyed this reading and the diversity in the different examples of information design. Two of the examples that stuck out to me were the 3D scatter plots and periodic table. I have previously never considered the periodic table as an example of design. It is so rooted in our curriculum and upbringing but presents a dense amount of information effectively. I found it fascinating because a lot of the design choices that led to this table (organizing different elements into groups based on properties, etc.) were made by scientists and probably not someone who was looking to optimize the visual appearance of the periodic table. Upon looking at the 3D Scatterplots for data and the oft-plotted data where the data was mapped onto six of the twelve surfaces of a pentagonal dodacahedron, I started to wonder how much of information design is rooted in past constructs + how willing are people to learn how to read something less intuitive but that could be potentially more structured. It also made me wonder about what the right balance between mimicking 3D/reality and our perception vs playing upon what we are used to that is based in that is rooted in some culturally taught phenonmenon (i.e. do I only think that periodic table is easy to read because I have been taught in science classes how to use it/its accepted culturally?).

Another piece that I really liked was The Art of Dancing which had a perspective map that coded gestures in dance notation of body motion. Visually, I thought the piece was very apealing even though I don’t know how to read it/what kind of dance is being conveyed. From this section, I was also really intrigued by the sentence “The redundancy of bilateral symmetry construmes space better devoted to fresh information”, because I never realized how inefficient symmetry can be when trying to display large quantities of data, especially because it can be attractive and pleasing to the eye. Even though the design is assymetric, it still felt very balanced and was designed in a way that I didn’t relaize it wasn’t symmetric upon a first glance. One last closing thought is I was really struck by the fact that humans have been using similar strategies of compressing information and displaying it on flat surfaces for centuries (i.e. mapping sunspots). We may develop technologies but the core principle hasn’t changed in the sense that we’re still here trying to better understand the world around us and communicate that to other people.

-

week 9-1 commentary- meenu singh

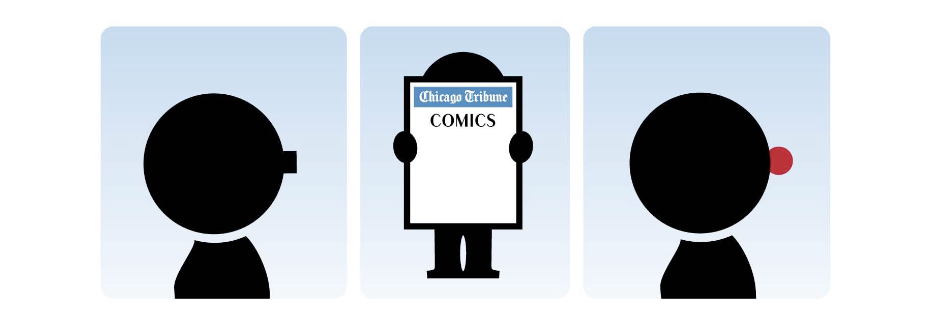

Chapter 4: Layering, Juxtaposition, and Scale

I thought this chapter was really interesting because it explained the process behind many of the design decisions that were made for the Talmud project. It made me more conscious of the way I process differnet streams of information. Traditionally, there isn’t an obvious spatial representation of how we mentally switch between multiple sources of information/different texts. The goal of the project comes down to displaying information from three different texts in a structure that is more intuitive and reflective of parallel thinking that occurs as we build connections between similar texts. To represent multiple texts on the same screen, Small utilized layering and added controls to shift the focal point of the display by varying different font features. I think this also connected well to a lot of the ideas we found in the master thesis, as the changin g of text blur with varying scales/sizes is rooted in interesting technical ideas. I found it very cool how blurry characters were computed in a manner that would require less storage by weighting two images and interpolating between them. It reminded me that the work necessary to have a dynmaic text that has smooth transitions is costly comptuationally and requires lots of work to optimize.

-

Tufte Flatland Response Mikel

Sunspot and train schedules were super confusing to me.

Even though I know nothing about music, the little sheet to teach dancing looked cool. I’m not sure how useful it would actually be, although the bit that dancer’s prefer symbolic notation over stick-figure poses was interesting. It makes me think about games like Just Dance where future movement is represented by figures on a timeline.

The weather map of Japan was interesting because of how it was designed specifically for the location, as Tufte said that this representation won’t be as useful for countries that aren’t thin. I wondered then if data in the California pollutant map works with the perspective it has. Not saying that it doesn’t, but I wonder if there are interesting areas of the map that are hidden by the angle.

I really liked the usefulness of small multiples, even though it felt like Tufte didn’t want to explain them, especially when talked about in regards to the colorful t-shirts. How easy it is to compare them is great, but the “active eye” idea engages a person more in the same way that investigating an image for more information can.

-

9.2 - Tufte Commentary - Trudy Painter

I liked Tufte’s intro to information design. I thought he synthesized the most important aspects data presentation (bountiful details with the capability for broad overview). Even though this book was published in 1990, the points were still relevant to today. Most of the examples of “good” information design I could have expected to see in the New York Times or some other big publication.

I liked that he brought up exploring multi dimensional data on computer screens. This is a point that feels especially relevant to the field of machine learning and model explainability. I had never seen a pentagonal graph and thought it was super cool. I honestly still don’t really know what it was plotting but had never seen a graph like this.

. The stereo illustrations felt novel, but I couldn’t even understand the example given. I wasn’t sure how stereo illustrations could be applied to tabular data.

Tufte’s continuation of flattening complex information felt weak addressing the more complex problem of visualizing interconnected high dimensional data. I hope future chapters present more approaches for dealing with abstract multivariate data.

-

Week 9.2 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

I found the stereoscopic pair of images very interesting, because even after staring at it for multiple minutes I couldn’t seem to see what I was supposed to see. It made me wonder what kind of viewers are more likely to be able to see the intended effect (maybe it has something to do with vision/eyesight?) and how it was used at all given that even experienced viewers often had trouble finding the right images.

The next section on representing data was much more confusing to me, and I found the sunspot example and the railroad example difficult to follow. However, I liked the air pollutant chart because it reminded me of the automatic 3D plots created in excel, and the fact that multiple graphs of similar structuere were placed side-by-side (“a small multiple”) made it easy to notice the changes across time.

I had conflicting thoughts on the “diamonds were a girl’s best friend” poster. Like the author, I didn’t particularly like the poster and thought the message that the poster was trying to send was unclear. However, I disagree with the author’s criticism that decorating a graph/source of information automatically makes it less trustworthy and is patronizing towards the viewer. I feel like there are graphs that add flourishes to numbers/information while still retaining the validity of their information, so it felt harsh to judge these creative displays as a group based on one bad example.

-

Week 9.2 Commentary - KCG

I found the stereo illustrations to be very interesting. At first, I wasn’t seeing the 3D scene, but then I went cross-eyed and eventually say it. However, I’m unconvinced that that image gave me any more information about the depth of the scene than each image viewed separately. It honestly felt more like I was looking through a magnifying glass or lenticular printing.

I found the sunspot and Java railroad line examples to be impossible to follow because they were too complex. The Japanese weather diagram was easy to follow because the symbols are pretty much stand-ins for their meanings (a sun means sunny, etc). Even though I am not familiar with the topography of Japan, I could still make out where the weather corresponded to what location just based on geography and relativity to the north and south ends of the islands (and of course aided by the text, too).

However, it is not just sheer amounts of data/the presence of numbers that led me to draw that conclusion, because I really liked the stem and leaf plot that depicted the heights of 218 volcanoes. Objectively, 218 data points is on the same magnitude as the data portrayed in the sunspot and railroad line example (albeit the data is more one-dimensional), but I found the stem and leaf plot to be easy to navigate, and it also gave me a good sense of the height distribution.

I thought the chart from United States v. Gotti to be very interesting, because as Tufte wrote, in terms of space, only 37% of the boxes are marked, and yet because of the long steaks (such as under Polisi) and because of the accumulation of marks under more severe crimes which are listed at the top, the mind draws the conclusion that there is a lot of criminal activity going on.

-

Week 9.1 Commentary - Audrey Gatta

David Small - Expressive Typography - PhD Thesis - Chapter 4

In this chapter, David Small discuses layering, juxtaposition and scale within digital media, describing the computer as intelligent paper, as it “can be programmed to intelligently react to changing inputs and models of both information and the user.” I liked the way he described this, with paper not being able to know what is printed on it, whereas a computer can. Several of the concepts that Small talked about show how computers have evolved significantly since 1999. For example, he says that the resolution is much worse on screens when compared to paper, but that is definitely not the case anymore. Small also emphasizes the limitation that “only the information in the topmost window is visible” on a computer screen, but now we can have split-screen views and multiple windows visible at once (also with smoother transitions from one to another).

I thought that Small’s continuous comparison to the design of a Talmud study tool to highlight the concepts of layering, juxtaposition and scale was very effective. I was specifically drawn to emphasis he places on the “dynamic context” of the computer and how “the elements are in a continuous state of change.” This brings the biggest difference to traditional graphic design, in which objects, as well as their relationships, are fixed. In terms of scale, Small shows how it opens up a new realm of possibilities, with scale no longer having to tie back directly to the relationship to the human form. Now, with the dynamic model that allows us to zoom and move elements around, “we are free to explore a vast range of scales.”

-

Week 8 - David Small, Hanu Park

In chapter 4, I find that through the process of anti aliasing, which is to make appearances more fuzzy, we as readers get the impression of clarity. It makes sense for larger font scales, since as the size increases, the jaggedness of the font becomes more obvious and less readable. To try and udnerstand what is happening, I think of it as scaling the slope of the diagonals into readable levels.

I went and found this image that demonstrated this idea since there were none in the chapter. The concept of anti aliasing was familiar because it often pops up in many video game settings! It is used in the same way, and has great impact on the graphics of the game.

-

[chxchen] Commentary 14: Tufte, Envisioning Information Ch. 1

This reading was pretty interesting and included a lot of cool historic examples of visual information. The introduction on the dimensionality of visual information made a lot of sense to me, and the Japanese travel guide aligned with what Tufte mentioned. I thought that the use of dimensionality in the travel guide was really interesting. The transition from 3D to more 2D flatland already gave an interesting mix of dynamic perspective along with typical map information, and the addition of the completely flat train map on the side added another dimension to how the map could be interpreted.

I also liked the examples of mapping over time – for example, the sunspots map, dots on a disc over time, and the train timetable. The mapping of information over time is a very interesting concept to me, and I liked how these examples could be aggregated to extract more information. The complexity and dimensionality of the train timetable was also pretty intriguing, though I didn’t look too deeply into the specific details. I think it works really well for organizing complicated logistical information where all operators need to be intimately familiar with these intricacies, but works less well to an outside viewer that needs quick access to pertinent information.

-

Week 9.1 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

Chapter 3 (form)

Throughout the chapter, I found the author’s description of the Shakespeare project very interesting. On one hand, it was cool to see how the virtual format allowed the text to be displayed in creative, unconventional ways, with each act of the Midsummer Night’s Dream floating in 3D space and each character’s dialogue being displayed in a different color. It reminded me of the video we watched in class last week, where he argued that since the virtual text is not limited to the constraints of paper text, we’re missing out on a huge opportunity by continuing to display text in a conventional, paper-like way. It made me think of reading apps like Kindle which try to mimic the paper reading experience as much as possible rather than be creative with their displays as a comparison to his virtual text displays. While I think these types of 3D text displays are very fun to navigate, it did may me question the legibility of the text and if it may end up hindering the reading experience rather than enhancing it. In this chapter, he does address the concern of different angles, orientations, and speeds of the display making it difficult to read, and suggests varying type sizes and limited movement as solutions. Still, Shakespeare’s texts are already so dense that zooming out and having multiple acts overlap seemed a bit disorienting, and I wondered if our eyes would get tired after reading the 3D text for a while. I think it would be really interesting to see his ideas on shorter texts like poetry or short stories.

-

Week 9.1 Commentary - Isabel Báez

Chapter 5: Expressive Movement

In his Expressive Movement chapter, David Small elaborates on how the movement of dynamic text is perceived by an audience. He dives into a description of the Minsky Melodies, in which music and text were combined to create an audio-visual experience. His description of fitting the text to the tone of the song, reminds me of Synesthesia, a condition in which certain music causes an individual to see shapes and colors. Moreover, his description of accurately timing the text so they were perceived as in par with the music reminds me of lyric videos; specifically, the idea of performing karaoke: where the timing of the text in conjunction with the music is crucial.

Small also gives into how sequential dynamicism of text enhances reading speed inviduals, and how this may mean that by enhancing the effictivity of a text’s movement, you are also enchancing its readibility. But he doesn’t just stop at tempo: he analyzes the influence of tone as well.

All in all, he creates a very intersting dynamic with sound an text. So far, our discussion has focused more on the visual movement representations of text and letters. Adding sound, music, and dictation to it adds an additional dimension that affects its perception. However, what is the line between this sound-driven text, and, say, a set of subtitles in a film? Or between it and the use of a kareoke machine as previously mentioned?

In the last section of this chapter, he discusses the Stream of Conciousness project. I found this work to be very intersting, as they use the flow of the water to have the audience interact with the text itself. The idea of word association, however, is a little lost on me. I would think that visitors of the space are more likely to play around with the letters, and arbitrarily see what other words are formed that directly meditate and associate with the words they first perceived. Regardless, the idea of the garden gives an erthereal feeling that, together with the interactiveness, clearly separates it from the idea of lyrics and/or subtitles. In this scenario, the sound at hand are the flows of the water, which are not directly connected with the words themselves, as is the case for the songs.

-

Rethinking the Book Chapter 3 - Mikel

I think I liked the analogy Small made between information landscapes and gardens, and also that the design of a space must be fitted to the content it will display. I think that we mostly try to conform all the information we want to the basic layout of a page, and although there are probably modern attempts to display information in a 3d environment I can’t think of any. I liked this reading because I believe I had a better idea of what Small was trying to achieve. His in depth explanations of the different constraints and considerations they had while making the Shakespeare Project were very clear to me, and I think the 90degree footnote idea was a cool solution that felt more realistically usable than others. I think by looking at the specific constraints Small had to tweak and design around I understood better how a 3d information landscape could be innovative as well as functional.

-

[chxchen] Commentary 13: David Small, Ph.D. Thesis Ch. 4

I read Chapter 4 of Small’s Ph.D. Thesis on Layering, Juxtaposition, and Scale. I really liked this chapter and thought it tied in well with the previous Small reading we did, and I can definitely see similar ideas as well as some progression.

Small starts out by discussing the difference between print and digital visual design, and I particularly find it interesting how Small claims that the latter has worse resolution – I can definitely see how this was the case previously, but I think digital work has gotten much higher in resolution.

Small discusses the Talmud project, addressing the issue of working with multiple texts simultaneously. The criteria for the project was creating a digital space where relevant texts could coexist, with material easily accessible (like flipping through a book). Small discusses the difference between physical and digital visuals in length in this section. Again, I found it interesting that he claims the main advantage of physical materials is the high resolution and how easy it is to compact many pages into one source of information like a book. Technology has definitely advanced to the point where we’re a lot better at data storage now, and websites can store a lot more than books can. The advantage of being dynamic and responsive remains the same. This also made me wonder about how Small views the existence of digital reading material that resembles physical ones, namely items like the Kindle.

Small also discusses layering as a method of controlling focus – by taking advantage of layering, we can shift user attention to different information centers. I found the discussion of the technical limitations to something like blurring quite interesting, because this process is definitely a lot faster now and more feasible to do.

Finally, Small discusses dynamic juxtaposition and scale. I didn’t really buy into his dynamic juxtaposition examples, particularly due to the emphasis on translated texts. Since most translations can’t happen word to word or even line to line, this kind of juxtaposition wouldn’t benefit the reader anyways. I think it’s worth also delving into non-Western-centric examples – for example, how can we digitally visualize both English and Chinese texts, with their different methods of reading (left-right vs. right-left). I liked the section on scale because one of the areas Small discusses is pretty relevant to modern design – the idea of persistence and allowing users to see multiple things on a screen at once. Many web browsers now support split screen and responsive sizing is an important element of UI design now.

-

Week 9.1 Commentary - KCG

I really don’t like these readings because I think they are quite dense and honestly a little contradictory. For instance, I thought the definition of “good text” that Small uses for this thesis to run contrary to my understanding of expressive text so far based on our readings on text/fonts and expressive and kinetic text. His definition, adapted from Jan Tschichold, only maintains that “good print” should be pleasing to the eye, and “should not attract particular attention” implying that if it does, then the print will “fight against the words it must convey.” However, based off of our other readings in this class thus far, the argument has been the opposite, in that fonts and kinetic text can aid the meaning of the content of the text - that the form of the print can be an additive to the meaning, rather than it being passive and deferential to the meaning.

-

9.1 - David Small Thesis - Trudy Painter

Chapter 2

Small outlined the history of reading machines. He started at the scroll, moved onto the printing press, then into book bindings, into the memex and hypertext, then finally webpage and screen-based mediums. I liked his point that the physical basis of the page has been replaced with the notion of a window. He also argues that dynamic typography is useful to place emphasis or save space in pages. I thought the linkage between dynamic typography and screen document was argued more effectively than in his master’s thesis.

Then, he moves into Muriel Cooper’s work with information landscapes and her project that used 3D flight to explore 3D dynamic typography. He also points out some issues with text in 3D (vanishing perspectives, inconsistent sizing, etc).

Here’s my thing: I don’t think text is meant to be the cornerstone of a three dimensional environment. Maybe some word art for a logo could be novel and fun. But, I think text works best in two dimensions. In recent virtual reality demonstrations, I’ve been unimpressed by the incorporation of text based content (and even pictures). For example, during quarantine, lots of museums tried to make virtual reality mediums. However, they were at best just 2D signs of text / paintings floating in 3D space. And whenever the type was dynamic, it was difficult to read.

This is an example of hypertext reimagined in 3 dimensions. It does a better job of communicating the scope and size of the content in its collections. How would it feel to be in a physical space with this content? However, navigation is difficult, and I always have an itching feeling of disorientation.

-

Week 8.2 Commentary (Isabel Báez)

Small discusses the importance of maintaining the idea of types and their dynamics in a digital context. Around the time this was written, computer graphics were not very developed, and the portrayal of text was very simple and plain. The urgency behind Small’s paper makes sense in this context. He discusses the importance of advancing these technical components to ensure that types become rich in a digital medium. He hypothesizes, and rightly so, that the digital medium will become prominent in design. Therefore, not developing these procedures to exploit types in this context puts them at a risk of losing their characteristics and richness. It is quite impressive to see Small predict the future for digital design so accurately. He mentions the need for speed in programs meant for design, which is certainly a high priority in any program that is created digitally today.

Moreover, he discusses the procedure behind dynamic simulation. These processes and calculations are what enable animations in today’s day and age. The diagrams shown for these movement of bodies are very similar to the logic used in programs such as Adobe Animate.

-

Week 8.2 Commentary (Rachel Chae)

I never quite realized how much physics and systems engineering goes into simulating motions—not only do computer systems have to calculate each pixel at a time but it also needs to make sure that there is a memory to hold those calculated values and that the computations are fast enough to display in real-time. Especially in the “wet fonts” section, I saw how much calculations go into simulating watercolor brush strokes, and it made me grateful for apps like photoshop and procreate that let me bypass the whole process and skip to the result. Reading the paper written with 90s technology in mind also made me recognize the advancement of visual design tools since then. Hearing about how multiple servers and sound systems had to work together to create something that can now be done by one person in adobe made me realize how many tools we take for granted.

It was also exciting to see that many of the works mentioned in his conclusions/future works section have come to fruition, such as a robust text editor or the simulation of bristly brushes. One area that I think may still be in the process of being realized is the dynamic comment linking and annotations. The way he described it made me think of google doc and word document comments, but I’m not sure if either of them exactly matches the approach he was proposing in the paper.

-

week 8.2 commentary - meenu singh